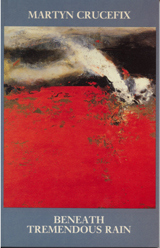

I was taken by surprise last week when BBC Radio Three contacted me to let me know that a line of poetry from a piece I’d published in Beneath Tremendous Rain back in 1990 has been used as the starting point for a Slow Radio programme, broadcast on the 17th May 2019, but available here for a month or so.

The connection was radio producer, Julian May, who I have worked with on several BBC radio programmes over the years. If you follow the link above, you’ll see Julian was responding to the opening two lines of the sequence of four poems which I will post in full below. His aim was to create a piece – ‘The Water’s Music’ – from recordings of the natural world.

Do listen to the programme – it’s just 30 minutes in length and the first half of it consists of Julian and the sound artist and musician, Tim Shaw, splashing about in a Northumbrian burn to record the astonishing variety of sounds produced by it. This is all a little bit bonkers, of course, but the sense of the great outdoors, the evocation of the water’s flow – beside, across, above and below – is marvellous, and does what Slow Radio often does, opening out the listeners’ sensibility in a playful, vivid and open-ended fashion.

The final, edited piece begins at 15.30 if you wanted to listen to that bit alone. I found it curiously moving that a thought – and a form of words I had in mind so many years back – has now been given aural form. The ‘music’ is also brilliantly in keeping with the poem. As you’ll see below, the epigraph is a quote from Marc Chagall, putting a premium on fluidity as opposed to precision and the idea that the artist/writer’s role is to approach something which is really inexpressible is a core belief that has remained with me over the years. The culmination of this view of art (I can now see) is my version of the great Ancient Chinese classic text the Daodejing which I published with Enitharmon in 2016.

As expressed in the poem, water still remains a god for me – I can never pass a fishmonger’s stall without stopping to gaze at the “wealth of silver”. The interesting graveyard inscription in the second poem (“Your ship, my love, is now mored / hed and starn for a fuldiew”) seems to be there to represent the fixity that all the images of water are in contrast to. Its words still affect me greatly: the lover’s desire for the permanence of what is quintessentially human being gradually eroded by the rain and the years. I will have had Thomas Hardy partly in mind, I’m sure, although the inscription I think is probably one I saw in Ireland many years ago.

The third poem contains memories of the Canary Islands – the island of Gomera, much more of a tourist haunt now than it was back then – and of the English Lakes in the fictional waterfall of Swirl Force, surely a version of the (again much-visited) Aira Force, beside Ullswater Lake (the same lake that recently featured in the concluding poems of my blog-posted but as yet unpublished sequence ‘Works and Days of Division).

I’m now amazed at how ‘Daoist’ the fourth and closing poem seems. It is a shock – largely in the sense that perhaps one keeps on re-writing the same poem for a lifetime. The concluding lines certainly express a great deal about how I’ve viewed poetry in the ensuing years – a grasping towards something which I know will always remain elusive; but achieved only through language – that monument to the human wish for and effort to achieve greater control and precision – can something of the fluidity of what is real be evoked: “I carry something of water / that in my hands must leak away – see / its silver threads ceaselessly falling.”

Here’s the poem in full:

Water Music

Divine fluidity, now that is truly precise – Marc Chagall

1.

I am a potter whose habitation

is beside the water’s music.

Its glittering’s, its clear truckling’s

endless fascination for me

might be the pull of like to like,

the riptides and rivers of my

almost nothing but water body.

Someone has said it’s the lure

of oblivion, pressing me to bow

and snort the sharp stunning solid

of water into my head,

that with a brief flickering

of its long-fixed content

would scour my mind clean forever.

Perhaps. Or something still

unevolved, still amphibian, wanting

to be rid of this self-consciousness

that cripples me – to shiver

a moment with mother-of-pearl,

folding of currents, sands, slime,

the swordfight of refracted rays.

At least I know my fascination

for the fishmonger’s wealth of silver,

that he is a diversion I often make,

though I cannot catch

any message his charges bring.

2.

Water has always been a god.

I fell in love with it as a boy,

would sit close by with the dusk,

determined to hook from it specimens

and secrets, calling to it

with words I’d let no adult hear.

Its glassy voices broke out

though too obscurely for a reply.

On the flaming beach at Thalassa,

where the crumbling glint of waves

marks the sea’s edge, I once

wanted to meet it open-mouthed,

though not driven by any love

of the cold confines of the drowned.

I hoped that I might simply

receive the unbounded horizon.

At the graveyard there is a stone

set by a girl for her dead sailor:

Your ship, my love, is now mored

hed and starn for a fuldiew.

Below, the etched ship is lashed hard

to the quay – all else has grown

too old and faint to be understood.

The rain is rubbing her words away.

3.

Then it’s everywhere with beauty,

at one with the darkness and moonlight

of the old poets for it transports us.

But I’ve seen it bending an iron bar.

The quiet cowl of October’s fog confuses,

comes to question the formulations

we keep – like the traveler who told me:

the hills of Gomera disappear for days

till the rain washes its own window clear.

At Swirl Force, under whitening hammers

of waterfall, everything is broken loose

and then the clouds’ anchors are weighed

and the dance starts up over the water:

every swollen-cheeked changeling face

stares at itself and floats away

with its glimpse on the heart of things.

4.

In my coercive dreams, there I am

pouring water into every available bowl

and setting them down as finished works.

I will have things as I want them,

though it is clear from whatever place

the water comes the bowls suffice –

though set to the river, their contents

fly to its night, are lost completely.

The river takes all that comes.

The river gives all that there is.

For I am a potter whose habitation

is beside the water’s music, who is

driven to his creations just as

the river is to its own. When I clasp

the rounded belly of a brimming bowl

I carry something of water

that in my hands must leak away – see

its silver threads ceaselessly falling.