Last week I was invited to take part in an on-line discussion about Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, written to a young would-be poet in the early 1900s. This event was organised by the Kings Place group, Chamberstudio, and the panel included two other poets, Martha Kapos and Denise Riley, musicians Mark Padmore, Amarins Weirdsma and Sini Simonen and composer Sally Beamish. We had such a fascinating discussion on Rilke’s advice to young artists (though perhaps we hardly scratched the surface) that I wanted to re-visit it and re-organise my own thoughts about the letters; hence this blog post. Though warm in tone and supportive, the letters are a way of Rilke talking to himself, developing coherent ideas that can be traced through the New Poems (1907/8), Requiem to a Friend (1909), even to the Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus of 1922. I am quoting throughout from Stephen Cohn’s translation of the letters, included in his translation of Sonnets to Orpheus (Carcanet, 2000).

Rilke’s advice to Franz Kappus was evidently received with gratitude as the correspondence between them continued (if sporadically) from early 1903 to December 1908. We don’t have Kappus’ side of things, but from Rilke’s comments it’s clear the younger, aspiring poet’s letters were remarkably open, even confessional in substance, as suggested by the published letters’ recurring observations about sexual relations. But as for practical advice to a young poet, Rilke offers little, opening with, “I am really not able to discuss the nature of your poems” to “You ask if your poems are good poems . . . You doubtless send your poems out to magazines and you are distressed each time the editors reject your efforts . . . my advice is that you should give all that up”. Probably not what Kappus hoped to hear, though he will have quickly understood that Rilke has more profound points to make. But it means these letters ought to be read less as advice to aspiring writers and more as advice on the best ways to ripen (Rilke’s metaphor) the inner self, a consequence of which might be the conviction that creative work was a necessity for the individual. Peter Porter once suggested a better title for the sequence would have been, ‘Letters to a Young Idealist’ (Introduction to Cohn’s Carcanet translation).

The advice given is carefully positive – what to seek – and fulsomely negative – what ought to be avoided. Friendly and remarkably sympathetic as his tone is through the series of letters, what Rilke asks, in truth, is extraordinarily demanding for mere ordinary mortals. Rilke urges a priest-like devotion to his High Romantic, Godless programme. In brief, what is to be sought is a clear, honest and open relationship with one’s own inner life and that demands a corresponding avoidance of everything that might distance us from it, especially the pernicious influence of social and cultural conventions, what has been thought, said, written or done before. Rilke makes no bones about how difficult the former is and how frightening the latter is going to feel.

The only way, Letter 1 insists, is to “go inside yourself”. And in Letter 3, we need to “allow each thing its own evolution, each impression and each grain of feeling buried in the self, in the darkness, unsayable, unknowable, and with infinite humility and patience to await the birth of a new illumination”. For reasons discussed later, there has to be a degree of passivity about this process: we must “await with deep humility and patience the moment of birth”. In his reply, Kappus must have enumerated the pain and suffering he was experiencing as a young man because Letter 8 spins this positively: “did not these sorrows go right through you – and not merely past you? Has there not been a great deal in you that has changed? Were you not somewhere . . . transformed while you were so sorrowful?” These often rough inner weathers of our emotional lives are precisely what is required. Only then, “something unfamiliar enters into us, something unknown; our senses, inhibited, and shy, fall silent; everything within us shrinks back, there is silence, and at its centre this new thing, strange to us all, stands mutely there”. In one of several memorable images, Rilke explains, through such emotional experience (the pains as much as, or even more than, the pleasures) “we have been changed as a house changes when a guest enters it”.

Those familiar with Keats’ ideas (expressed in his 1819 Letters) about the world as a ‘vale of soul-making’ will find something very familiar here. But Rilke’s take on the process of ‘spirit creation’ lays far heavier emphasis on the need for solitude to achieve it. Letter 5 tells Kappus, “win yourself back from the insistence of the talk and the chatter of the multitude (and how it chatters!)”. The chattering world is a distraction from what ought to be the subject of our study (our inner selves): “What is required is this: solitariness, great inner solitariness. The going-into oneself and the hours on end spent without encountering anyone else: it is this we must be able to achieve” (Letter 6). Such solitude enables greater concentration but also more true (uninfluenced) perception of our inner life. Yet to turn away from so much that is familiar will be frightening. In Letter 8, Rilke compares this to someone “plucked from the safety of his own small room and, unprepared and almost instantaneously, set down upon the heights of some great mountain-range”. What must then be experienced is “a never-to-be-equalled sense of insecurity, of having fallen into the power of something nameless [and this] would virtually destroy him”.

The negative influences of those (us, the timid majority) who have pulled back from such a state of perception is explained. Rilke’s basic tenet is that we are all “solitary”. But the uncertainty of a ‘true’ perception of this is too much for most people: “mankind has been pusillanimous in this respect [and] has done endless harm to life itself: all phenomena we call ‘apparitions’, all the so-called ‘spirit-world’, death, all these things so closely akin to us have been fended off . . . and so thoroughly purged from our lives that the senses by which we might have grasped them have atrophied. To say nothing at all of God”. What Rilke describes here are a number of the conventional ideas – pure figments about the truth of spirituality, death and a deity – that people have populated their world with in seeking greater security. Kappus is told, “a perilous uncertainty is so very much more human” and the truly human, let alone the ambitious poet, must accept the principle that “we arrange our lives in accordance with the precept that teaches us always to hold to what is difficult – then everything that still appears most alien will become all that is best-trusted, most dependable”. Rilke’s chosen metaphor here is the folkloric/mythic image of the terrifying dragon that turns into a rewarding princess at the last moment.

Herein lies also the wisdom of passivity. As Keats argued in parallel, with his idea of negative capability (the knack of remaining “in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”), so Rilke’s fourth Letter advises Kappus not to seek out answers now but to “love the very questions, just as if they were locked-up rooms or books in an utterly unknown language”. The key is to “live them” by which Rilke (like Keats) means to examine and attend to them as fully as possible. He goes so far as to advise a child-like incomprehension (which is at least based on an openness to the questions asked) over a cowardly defensiveness or contempt (which falls back on a distancing from those questions). This is why, in Letter 2, he sharply advises Kappus to avoid irony. There are, says Rilke, “great and serious subjects before which irony stands helpless and diminished” because irony is, by definition, a standing outside of a question or topic. For the same reason, Rilke distrusts engagement with literary or aesthetic criticism (precisely what Kappus has asked of him in relation to his own poems). Letter 3 argues such critical discussions are “received opinions, opinions grown petrified and meaningless, insensitive . . . clever word games”, hence far distant from life itself. The same Letter suggests the artist needs to retain an innocence, even a lack of awareness of his/her creative powers, lest self-consciousness diminish freedom and “purity”. Indeed language itself – the common method of exchange between people – is suspect in representing, in its unexamined use, conventional thought and feeling: “it is so often on the name of a transgression that a life is shipwrecked, and not on the individual, nameless act-in-itself”.

Even these letters, Rilke says in Letter 9, need to be treated with caution and patience: “receive them quietly and with not too many thanks, and let us, please, wait and see what may come of them”. This is a warning not enough heeded by subsequent generations of readers, but Rilke’s real humility is re-emphasised at the end of the preceding Letter. Perhaps feeling he has been delivering advice from ‘on high’, Rilke warns Kappus, “do not believe that he who seeks to console you dwells effortlessly among the quiet and simple words which sometimes content you. His own life holds much trouble and sorrow, and it falls far short of them”. Surely Rilke is not merely alluding here to the life of the creative artist. Prompted, as I have said, by Kappus’ own openness about what we might call ‘romantic’ aspects of his own life, Rilke devotes a lot of space to interpersonal relationships in these letters. His point in Letter 7 is that this area of human life too is poisoned (“well-furnished” – this topic brings out Rilke’s satirical side) with conventional thinking and language: “here are life belts of the most varied invention, boats and buoyancy packs . . . safety aids of all conceivable kinds”. Such ‘safety’ features are more fictions designed to forestall a true encounter with the kinds of questions that human relationships inevitably throw up. Letter 3 particularly criticises male sexual attitudes (lustful, drunken, restless, arrogant, prejudiced) and Letter 7 anticipates a “new and individual flowering” of female sexuality which will lead to relationships not defined as male/female but as “one person and another person”.

Such a renovation of individuals, from the inside out, is the urgent call of this series of letters. As to advice to Kappus the wannabe writer, Rilke offers very little, but what he does suggest is wholly in keeping with his other ideas. Letter 1 urges close observation as the only viable method. As I have made clear, this is especially close observation of our inner lives. But one’s whole life needs to be built around this principle, so “you must approach the world of Nature… try to tell of what you see and experience”. Rilke says don’t try to write love poems or on other common subjects of poetry. This is because they will be infected with those conventions of thought and expression I have discussed above. Rather, “favour the subjects which your own day-to-day experience can offer you”. The poet’s approach to such everyday subjects needs to be “quiet, humble, [with] passionate sincerity” to avoid clichés of thought and feeling, hand-me-down solutions or worn out, petrified language. These are the methods Rilke learned from watching Rodin sketching in Paris. Pre-empting likely objections that such an approach would produce work of little importance, Rilke goes on: “If your daily life seems mean to you – do not find fault with it; rather chide yourself that you are not poet enough to evoke its riches” (Letter 1).

The everyday is rich and complex enough for Rilke without any irritable searching after more conventionally dramatic, sensational, controversial subjects to address. The images that Letter 3 associates with this humble creative process is of gestation (“to carry, come to term, give birth”) and the slow growth of trees (“letting the sap flow at its own pace”). In Letter 6 he compares it to bees gathering honey (“drawing what is sweetest from all that there is”). Whether focusing within or without, the artist must begin from what is “unremarkable” and we become better acquainted “with things” and if this is too frightening a prospect – with no off-the-shelf solutions to human fears and insecurities, no God above all – Rilke has few comforts to offer the young poet. As regards God (or, as letter 6 refers to him, the “one who never was”), Rilke allows the idea of God only as the ideal or terminus towards which we travel, a state of full comprehension – through knowing humble things: “Does he not have to be the last, if everything is to be comprehended in him? And what meaning would there be in us, if the one we crave had already been there?”. God, for Rilke, does not pre-date us as an origin. He is the goal towards which we travel, aspire, build, create – ‘he’ is no more nor less than our fullest comprehension of life and death, hence our fullest sense of being in the world.

That the young Franz Kappus, after all this, decided to pursue a military career rather than a creative one is perhaps hardly surprising. It may be that the former presented the least frightening option! Rilke asks such a lot. His poem Requiem to a Friend of 1909 (the year after his correspondence with Kappus came to an end), dwells on the “old enmity / between life lived and great work to be done” (tr. Crucefix). The tragic lament of that particular poem arises from his conviction that the subject of its in memoriam, the painter Paula Modersohn-Becker, had proved herself strong enough to carry forward the huge burden of being an artist and that, therefore, her untimely death (just after the birth of her first child) was an irreparable loss to a world that needs all the true artists it can nurture.

I’m not proud to admit that Way More Than Luck passed me by when it was first published. As you are probably aware, Wilkinson reviews poetry regularly for The Guardian, and he’s very familiar on social media as a poet and critic, a distance runner and a passionate Liverpool football fan. But the book’s cover (Dalglish, I think), its title and some of the publicity persuaded me that the football bit was going to be predominant. It’s certainly an almost unique aspect of the collection, but it turns out the debilitating darkness of psychological depression is an even more significant one. Wilkinson signals this concern via the book’s two epigraphs. One is about the nature of depression

I’m not proud to admit that Way More Than Luck passed me by when it was first published. As you are probably aware, Wilkinson reviews poetry regularly for The Guardian, and he’s very familiar on social media as a poet and critic, a distance runner and a passionate Liverpool football fan. But the book’s cover (Dalglish, I think), its title and some of the publicity persuaded me that the football bit was going to be predominant. It’s certainly an almost unique aspect of the collection, but it turns out the debilitating darkness of psychological depression is an even more significant one. Wilkinson signals this concern via the book’s two epigraphs. One is about the nature of depression

For me, it’s these psychological truths that Wilkinson is so good at conveying. There are other poems later in the book (and perhaps ‘Stag’ is an elusive example) which begin to sketch episodes of a foundering romantic relationship and ‘Building a Brighter, More Secure Future’ is a very effective excursion into witty political satire (a skilfully handled sestina based on the Conservative Party election manifesto, 2015). And there are the football poems. They comprise the central sequence of 14 poems, introduced with a heart-felt Prologue that says what follows is for the ordinary football fans, written out of “a love beyond the smear campaigns, / the media’s hooligans”. A large part of what Wilkinson has in mind here is the shocking response in parts of the media to the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989, when 96 men, women and children died (David Cain’s Forward prize shortlisted book, Truth Street, from Smokestack Books, movingly dealt with this event and the media and policing responses and

For me, it’s these psychological truths that Wilkinson is so good at conveying. There are other poems later in the book (and perhaps ‘Stag’ is an elusive example) which begin to sketch episodes of a foundering romantic relationship and ‘Building a Brighter, More Secure Future’ is a very effective excursion into witty political satire (a skilfully handled sestina based on the Conservative Party election manifesto, 2015). And there are the football poems. They comprise the central sequence of 14 poems, introduced with a heart-felt Prologue that says what follows is for the ordinary football fans, written out of “a love beyond the smear campaigns, / the media’s hooligans”. A large part of what Wilkinson has in mind here is the shocking response in parts of the media to the Hillsborough tragedy in 1989, when 96 men, women and children died (David Cain’s Forward prize shortlisted book, Truth Street, from Smokestack Books, movingly dealt with this event and the media and policing responses and  But the poems also show how difficult it is to escape the miasma of cliché that seems to engulf football itself. Anfield is filled with a “fabled buzz”, then “the place erupt[s]”. Barnes unleashes a “a sweeping, goal-bound ball”, and a particular game offers one “last-ditch twist”. I’m reminded of Louis MacNeice’s observation (now sadly compromised in various ways, but the spirit of it remains valid, I think) that he wanted a poet not to be “too esoteric. I would have a poet able-bodied [sic], fond of talking, a reader of the newspapers, capable of pity and laughter, informed in economics, appreciative of women [sic], involved in personal relationships, actively interested in politics, susceptible to physical impressions’. There are many more of these poets around these days and to bring (even) football into the purview of poetry can hardly be a bad thing. Yet it is not an easy one and there may be some risks in deciding to headline the attempt. Ian Duhig’s blurb note to Way More Than Luck has gingerly to negotiate this issue: “The beautiful game inspires some beautiful poems in Ben Wilkinson’s terrific debut collection … but there’s far more than football to focus on here”. Yes, indeed.

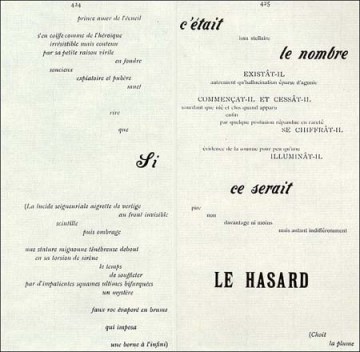

But the poems also show how difficult it is to escape the miasma of cliché that seems to engulf football itself. Anfield is filled with a “fabled buzz”, then “the place erupt[s]”. Barnes unleashes a “a sweeping, goal-bound ball”, and a particular game offers one “last-ditch twist”. I’m reminded of Louis MacNeice’s observation (now sadly compromised in various ways, but the spirit of it remains valid, I think) that he wanted a poet not to be “too esoteric. I would have a poet able-bodied [sic], fond of talking, a reader of the newspapers, capable of pity and laughter, informed in economics, appreciative of women [sic], involved in personal relationships, actively interested in politics, susceptible to physical impressions’. There are many more of these poets around these days and to bring (even) football into the purview of poetry can hardly be a bad thing. Yet it is not an easy one and there may be some risks in deciding to headline the attempt. Ian Duhig’s blurb note to Way More Than Luck has gingerly to negotiate this issue: “The beautiful game inspires some beautiful poems in Ben Wilkinson’s terrific debut collection … but there’s far more than football to focus on here”. Yes, indeed. I am very grateful to Ian Brinton’s and Michael Grant’s recent translation of a selected Mallarmé (Muscaliet, 2019) for sending me back to a poet who has always proved problematic for me. My natural inclination draws me more to Louis MacNeice’s sense of the “drunkenness of things being various” (‘Snow’) – his emphasis on poetry’s engagement with “things” – and his desire to communicate pretty directly with his fellow wo/man, than with what Elizabeth McCombie bluntly calls “the exceptional difficulty” of Mallarmé’s work. I appreciate that such a dichotomy seems to shove the French poet into an ivory tower (albeit of glittering and sensuous language) while casting the Irish one as too narrowly engagé, but I’m also aware that Sartre praised Mallarmé as a “committed” writer and that, despite some evident remoteness from the ‘tribe’, the French poet’s political views were both radical and democratic.

I am very grateful to Ian Brinton’s and Michael Grant’s recent translation of a selected Mallarmé (Muscaliet, 2019) for sending me back to a poet who has always proved problematic for me. My natural inclination draws me more to Louis MacNeice’s sense of the “drunkenness of things being various” (‘Snow’) – his emphasis on poetry’s engagement with “things” – and his desire to communicate pretty directly with his fellow wo/man, than with what Elizabeth McCombie bluntly calls “the exceptional difficulty” of Mallarmé’s work. I appreciate that such a dichotomy seems to shove the French poet into an ivory tower (albeit of glittering and sensuous language) while casting the Irish one as too narrowly engagé, but I’m also aware that Sartre praised Mallarmé as a “committed” writer and that, despite some evident remoteness from the ‘tribe’, the French poet’s political views were both radical and democratic. So, if we must give up on such ‘understanding’, what was Mallarmé – writing in the 1880-90s – doing? Something recognisably very modern, it turns out. Contra Wordsworth (and MacNeice, I guess), Mallarmé and his Symbolist peers, held ordinary language in suspicious contempt as too ‘journalistic’, too wedded to a world of facts. Poetry was to be more a communication, or evocation, of emotion, of a detachment from the (merely) everyday and a recovery of the mystery of existence which rote and routine has served to bury. Such a role demanded linguistic innovation as suggested in ‘The Tomb of Edgar Poe’ in which the American writer is praised for giving “purer meaning to the words of the tribe” (tr. Brinton/Grant). Writing about Edouard Manet’s work, Mallarmé saw the need to “loose the restraint of education” which – in linguistic terms – would mean freeing language from its contingent relations to the facticity of things (and the tedium and ennui that results from our long confinement to them) and hence moving language nearer to what he called the “Idea” and the paradoxical term Nothingness (as Brinton/Grant translate “le Neant”).

So, if we must give up on such ‘understanding’, what was Mallarmé – writing in the 1880-90s – doing? Something recognisably very modern, it turns out. Contra Wordsworth (and MacNeice, I guess), Mallarmé and his Symbolist peers, held ordinary language in suspicious contempt as too ‘journalistic’, too wedded to a world of facts. Poetry was to be more a communication, or evocation, of emotion, of a detachment from the (merely) everyday and a recovery of the mystery of existence which rote and routine has served to bury. Such a role demanded linguistic innovation as suggested in ‘The Tomb of Edgar Poe’ in which the American writer is praised for giving “purer meaning to the words of the tribe” (tr. Brinton/Grant). Writing about Edouard Manet’s work, Mallarmé saw the need to “loose the restraint of education” which – in linguistic terms – would mean freeing language from its contingent relations to the facticity of things (and the tedium and ennui that results from our long confinement to them) and hence moving language nearer to what he called the “Idea” and the paradoxical term Nothingness (as Brinton/Grant translate “le Neant”). For these reasons, Mallarmé “cede[s] the initiative to words” (‘Crise de Vers’), to language’s material aspects as much as to its referential functions. Carrying over the material aspects of his French verse into English is then, to say the least, difficult. I’m inclined to agree with Weinfield (Introduction to Stephane Mallarmé Collected Poems (Uni. Of California Press, 1994) that it is “essential to work in rhyme and metre, regardless of the semantic accommodations and technical problems this entail[s]. If we take rhyme from Mallarmé, we take away the poetry”. But is that even possible? The accommodations and problems that arise are huge! Mallarmé placed the sonnet, ‘Salut’, at the start of his Poésies as a toast, salutation and mission statement. Weinfield gives the sestet as follows:

For these reasons, Mallarmé “cede[s] the initiative to words” (‘Crise de Vers’), to language’s material aspects as much as to its referential functions. Carrying over the material aspects of his French verse into English is then, to say the least, difficult. I’m inclined to agree with Weinfield (Introduction to Stephane Mallarmé Collected Poems (Uni. Of California Press, 1994) that it is “essential to work in rhyme and metre, regardless of the semantic accommodations and technical problems this entail[s]. If we take rhyme from Mallarmé, we take away the poetry”. But is that even possible? The accommodations and problems that arise are huge! Mallarmé placed the sonnet, ‘Salut’, at the start of his Poésies as a toast, salutation and mission statement. Weinfield gives the sestet as follows: