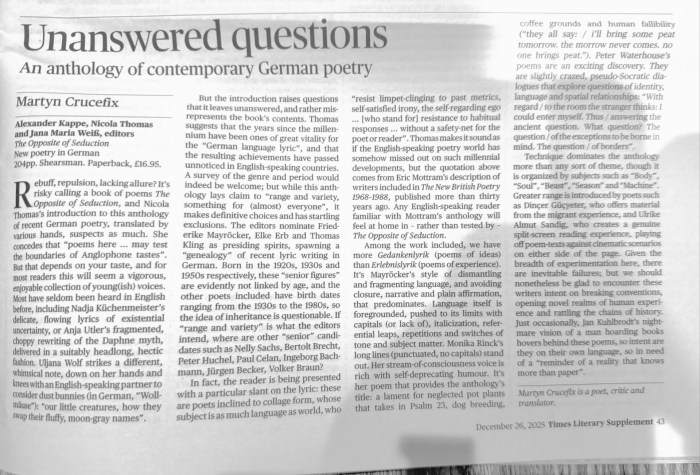

This review – or a shortened version of it – first appeared in The Times Literary Supplement, 25th December 2025. Many thanks to Camille Ralphs for commissioning it. The Opposite of Seduction: New Poetry in Germanis edited by Alexander Kappe, Nicola Thomas, Jana Maria Weiß and published by Shearsman Books, 2025.

Rebuff, repulsion, lacking allure – it’s a risk to call an anthology of poetry The Opposite of Seduction and perhaps Nicola Thomas’ brief Introduction to this book of new German poetry in translation suspects as much. She concedes, ‘poems here . . . may test the boundaries of Anglophone tastes’. But that depends on your taste and for most readers this anthology will seem a vigorous enjoyable collection of young(ish) voices, most hardly ever heard in English before like Nadja Küchenmeister’s delicate, flowing lyrics of existential uncertainty (tr. Aimee Chor), or Anja Utler’s sole contribution, a re-writing of the Daphne myth, exploiting the white page, a choppy fragmentation, exclamation, and a suitably headlong, hectic delivery. A different note is struck by Uljana Wolf, in her whimsical teasing away at self-awareness, waking at four in the morning, or down on hands and knees with an English-speaking partner, to consider dust bunnies (in German ‘Wollmaus’); ‘our little creatures, how they swap their fluffy, moon-gray names’ (tr. Sophie Seita).

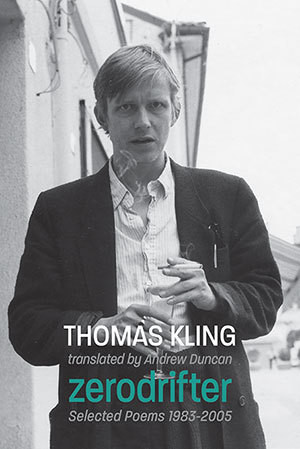

Yet despite its brevity, Thomas’ Introduction raises questions it leaves unanswered, rather misrepresents the book’s contents, and shows signs of revisions and deletions (it’s puzzling that her two co-editors do not put their name to it). She suggests the years since the millennium have been ones of great vitality for the ‘German language lyric’ and the resulting achievements have passed unnoticed in English-speaking countries for want of translations gathered in one place. A broad survey of the genre and period would indeed be welcome, but this anthology lays claim to ‘range and variety, something for (almost) everyone’, yet makes definitive choices and has startling exclusions. The editors nominate Friederike Mayröcker, Elke Erb, and Thomas Kling as presiding spirits, spawning a ‘genealogy’ of lyric writing in German. Born in the 1920s, ‘30s and ‘50s respectively, it’s not their age that links these ‘senior figures’ and because poets included in The Opposite of Seduction have birth dates ranging from the 1930s to the 1970s/80s, the idea of inheritance is at best questionable. If ‘range and variety’ is what the editors intended, then where are other ‘senior’ candidates like Nelly Sachs, Bertolt Brecht, Peter Huchel, Paul Celan, Ingeborg Bachmann, Jürgen Becker, Volker Braun, Durs Grünbein?

In fact, the reader is here presented with a particular slant on the lyric: these are poets inclined to collage-form, whose subject is as much language as world, who ‘resist limpet-clinging to past metrics, self-satisfied irony, the self-regarding ego . . . [standing for] resistance to habitual responses . . . without a safety-net for the poet or reader’. Thomas can make it sound as if the English-speaking poetry world has somehow missed out on such millennial developments, but the latter quotation comes from Eric Mottram’s description of writers included in the new british poetry, published over thirty years ago. So any English-speaking reader familiar with Mottram’s anthology of ‘marginalised’ poets will feel at home in (rather than tested by) The Opposite of Seduction.

As to the poems themselves, we have far more examples of Gedankenlyrik (poems of ideas) than Erlebnislyrik (poems of experience). It’s Mayröcker’s style (closely followed by Kling) of dismantling language, of fragmentation, the avoidance of closure, narrative, or simple affirmation, that is the order of the day. Language is foregrounded, pushed to its limits with capitals (or avoidance of), italicisation, referential leaps, allusions, repetitions, abrupt switches of tone and subject matter. Monika Rinck’s long prose-y lines (punctuated, no capitals) stand out. They carry a stream of consciousness voice with a self-deprecating humour. It’s one of her poems that provides the anthology title; a lament for neglected office pot plants that manages to encompass Psalm 23, dog breeding, coffee grounds and human fallibility: ‘they all say: / i’ll bring some peat tomorrow. the morrow never comes. no one brings peat.’ Iain Galbraith’s brilliant renderings of poems by Peter Waterhouse are also a revelation. His is a voice delivering slightly crazed, swift, pseudo-socratic dialogues as poems, wearing a sly smile, and exploring questions of identity, language and spatial relationships: ‘With regard / to the room the stranger thinks: I could enter myself. Thus / answering the ancient question. What question? The question / of the exceptions to be borne in mind. The question / of borders’.

Technique dominates rather than subject matter, though the selection is organised by subjects such as Heart, Body, Soul, Beast, Season, Machine, Home. Oswald Egger writes lush, musical celebrations of the natural world which in Ian Galbraith’s renderings evoke Hopkins, even Dylan Thomas. Dinçer Güçyeter brings material from the migrant experience (tr. Caroline Wilcox Reul) and Ulrike Almut Sandig creates a genuine split-screen reading experience, playing poem texts off against story board instructions either side of the page (tr. Karen Leeder). Given the breadth of experimentation going on here, there are inevitable failures. These are poets working to free both writer and reader from conventions, to open up novel realms of human experience, a liberation from history. Occasionally, Jan Kuhlbrodt’s nightmare vision of a man hoarding books and newspapers hovers behind some poems, so intent on their own language are they, perhaps in need of a ‘reminder of a reality that knows more than paper’ (tr. Alexander Kappe).