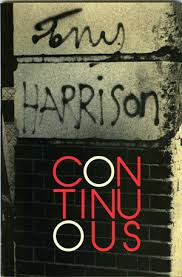

With the sad news of the passing of Tony Harrison, who as a working class poet had a great impact on me during my formative years of writing in the 1980s, I went back to a piece I was commissioned to write for an OUP collection of essays on his writing – both poetic and dramatic – in 1997. The book, Tony Harrison: Loiner, was edited by Sandie Byrne and included articles from Richard Eyre, Melvyn Bragg, Alan Rusbridger, Rick Rylance, and Bernard O’Donoghue. This is the full text of what I contributed: an intense focus on and close analysis of two of Harrison’s key poems, ‘A Cold Coming’ (for Harrison reading this poem click here) and ‘Them & [uz]’ (for the text of this poem click here).

The Drunken Porter Does Poetry: Metre and Voice in the Poems of Tony Harrison

Part I

Harrison’s first full collection, entitled The Loiners after the inhabitants of his native Leeds, was published in 1970 and contained this limerick:

There was a young man from Leeds

Who swallowed a packet of seeds.

A pure white rose grew out of his nose

And his arse was covered in weeds.

Without losing sight of the essential comedy of this snatch, it can be seen as suggestive of aspects of Harrison’s career. For example, the comic inappropriateness of the Leeds boy swallowing seeds becomes the poet’s own ironic image of his classical grammar school education. As a result of this, in a deliberately grotesque image, arises the growth of the white rose of poetry – from the boy’s nose, of course, since Harrison in the same volume gave credence to the idea that the true poet is born without a mouth (1). The bizarrely contrasting weed-covered arse owes less to the intake of seeds (rose seeds wherever transplanted will never yield weeds) than to the harsh conditions Harrison premises in the Loiner’s life, as indicated in an early introduction to his work, where he defines the term as referring to “citizens of Leeds, citizens who bear their loins through the terrors of life, ‘loners'”(2).

Harrison’s now-legendary seed-master on the staff of Leeds Grammar School was the one who humiliated him for reciting Keats in a Yorkshire accent, who felt it more appropriate if the boy played the garrulous, drunken Porter in Macbeth.(3) The truth is that the master’s attitudes determined the kind of poetic rose that grew, in particular its technical facility which Harrison worked at to show his ‘betters’ that Loiners could do it as well as (better than?) they could. Yet this was no sterile technical exercise and Harrison’s success lies in the integrity with which he has remained true to those regions “covered with weeds” and in the fact that his work has always struggled to find ways to unite the weed and the rose. Perhaps the most important of these, as the limerick’s anatomical geography already predicted in 1970, is via the rhythms of his own body.

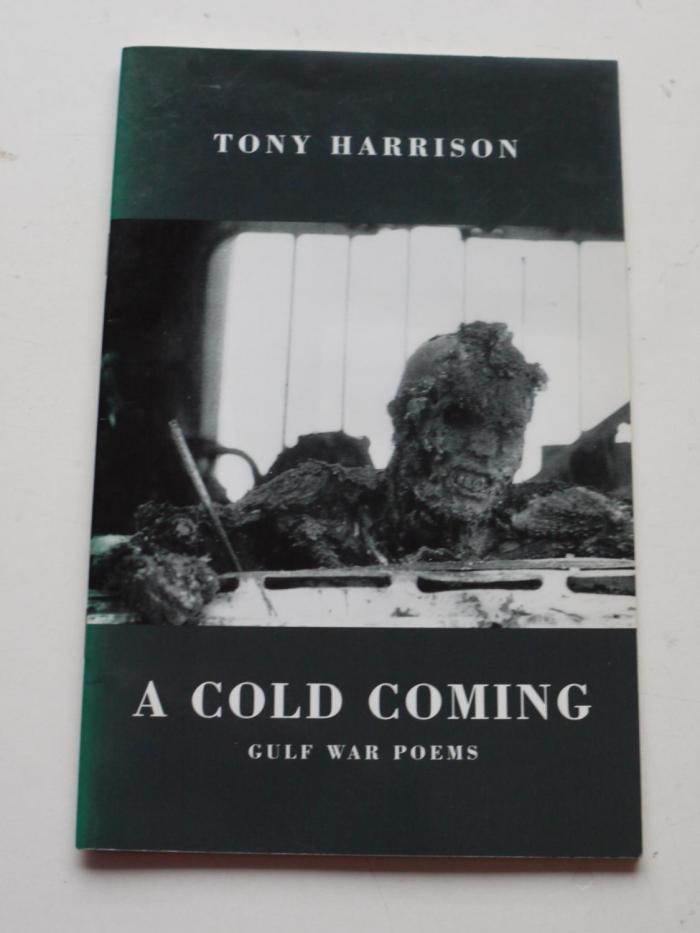

Harrison has declared his commitment to metrical verse because “it’s associated with the heartbeat, with the sexual instinct, with all those physical rhythms which go on despite the moments when you feel suicidal” (4). In conversation with Richard Hoggart, he explains that without the rhythmical formality of poetry he would be less able to confront, without losing hope, the unweeded gardens of death, time and social injustice which form his main concerns. “That rhythmical thing is like a life-support system. It means I feel I can go closer to the fire, deeper into the darkness . . . I know I have this rhythm to carry me to the other side” (5). There are few of Harrison’s poems that go closer to the fire than the second of his Gulf War poems, ‘A Cold Coming’ (6). Its initial stimulus, reproduced on the cover of the original Bloodaxe pamphlet, was a photograph by Kenneth Jarecke in The Observer. The picture graphically showed the charred head of an Iraqi soldier leaning through the windscreen of his burned-out truck which had been hit by Allied Forces in the infamous ‘turkey-shoot’ as Saddam’s forces retreated from Kuwait City. In the poem, Harrison makes the Iraqi himself speak both with a brutal self-recognition (“a skull half roast, half bone”) as well as a scornful envy of three American soldiers who were reported to have banked their sperm for posterity before the war began (hence, with a scatological nod to Eliot, the title of the poem). There are undoubtedly echoes in the Iraqi’s speech of the hooligan alter ego in the poem ‘V’, yet Harrison worries little over any narrow authenticity of voice in this case, and he does triumphantly pull off the balancing act between the reader’s emotional engagement with this fierce personal voice and a more universalising portrayal of a victim of modern warfare. Furthermore, it is Harrison’s establishment and then variation of the poem’s metrical “life-support system” that enables him to achieve this balance, to complete a poem which weighs in against Adorno’s view that lyric poetry has become an impossibility in the shadow of this century’s brutality.

The poem’s form – rhymed iambic tetrameter couplets – seems in itself chosen with restraint in mind, as if the photographic evidence of the horror lying in front of him led Harrison to opt for a particularly firm rhythmical base “to carry [him] to the other side”. Indeed, the opening five stanzas are remarkable in their regularity with only a brief reversed foot in the fourth line foreshadowing the more erratic energies soon to be released by the Iraqi soldier’s speech:

I saw the charred Iraqi lean

towards me from bomb-blasted screen,

his windscreen wiper like a pen

ready to write down thoughts for men.

The instant the Iraqi’s voice breaks in, the metre is under threat. Each of his first four stanzas opens with trochaic imperatives or questions and at one point he asks if the “gadget” Harrison has (apparently a tape-recorder but a transparent image of poetry itself) has the power to record “words from such scorched vocal chords”. Apart from the drumming of stresses in lines such as this, Harrison deploys sibilance, the alliteration of g’s and d’s, followed by an horrific mumbling of m’s to suggest the charred figure’s effortful speech in the first moments of the encounter. Regularity is re-established the moment the tape-recorder’s mike is held “closer to the crumbling bone” and there is a strong sense of release from the dead man’s initial aggressive buttonholing as his voice (and the verse) now speeds away:

I read the news of three wise men

who left their sperm in nitrogen,

three foes of ours, three wise Marines,

with sample flasks and magazines . . .

In the stanzas that follow, the dead man’s angry, envious sarcasm is controlled within the bounds of the form and it is rather Harrison’s rhymes which provide much of the kick: God/wad, Kuwait/procreate, fate/ejaculate, high tech’s/sex. It is only when the man demands that Harrison/the reader imagines him in a sexual embrace with his wife back home in Baghdad that the metrical propulsion again begins to fail. It is in moments such as this that the difficult emotional work in the poem is to be done. This is our identification with these ghastly remains, with the enemy, and it is as if the difficulty of it brings the verse juddering and gasping to an incomplete line with “the image of me beside my wife / closely clasped creating life . . .”

The difficulty of this moment is further attested to by the way the whole poem turns its back upon it. Harrison inserts a parenthetical section, preoccupied not with the empathic effort the dead Iraqi has asked for but with chilly, ironic deliberations on “the sperm in one ejaculation”. Yet all is not well, since this section stumbles and hesitates metrically as if Harrison himself (or rather the persona he has adopted in the poem) is half-conscious of retreating into safe, calculative and ratiocinative processes. Eventually, a conclusion yields itself up, but it is once again the metrical change of gear into smooth regularity (my italics below) that suggests this is a false, defensive even cynical avoidance of the difficult issues raised by the charred body in the photograph:

Whichever way Death seems outflanked

by one tube of cold bloblings banked.

Poor bloblings, maybe you’ve been blessed

with, of all fates possible, the best

according to Sophocles i.e.

‘the best of fates is not to be’

a philosophy that’s maybe bleak

for any but an ancient Greek . . .

That this is the way to read this passage is confirmed by the renewed aggression of the Iraqi soldier who hears these thoughts and stops the recorder with a thundering of alliterative stresses: “I never thought life futile, fool! // Though all Hell began to drop / I never wanted life to stop”. What follows is the Iraqi soldier’s longest and most impassioned speech, by turns a plea for attention and a sarcastic commentary on the collusion of the media whose behaviour will not “help peace in future ages”. Particular mention is given to the “true to bold-type-setting Sun” and, as can be seen from such a phrase, Harrison once more allows particular moments of anger and high emotion to burst through the fluid metrical surface like jagged rocks. There is also a sudden increase in feminine rhyme endings in this section which serves to give a barely-caged impression, as if the voice is trembling on the verge of bursting its metrical limits and racing across the page. This impression is further reinforced in the series of imperatives – again in the form of snapping trochees at the opening of several stanzas – that form the climax to this section of the poem:

Lie that you saw me and I smiled

to see the soldier hug his child.

Lie and pretend that I excuse

my bombing by B52s.

The final ten stanzas culminate in a fine example of the way in which Harrison manipulates metrical form to good effect. In a kind of atheistic religious insight, the “cold spunk” so carefully preserved becomes a promise, or perhaps an eternal teasing reminder, of the moment when “the World renounces War”. However, emphasis falls far more heavily on the seemingly insatiable hunger of the present for destruction because of the way Harrison rhythmically clogs the penultimate stanza, bringing it almost to a complete halt. The frozen semen is “a bottled Bethlehem of this come- /curdling Cruise/Scud-cursed millennium”. Yet, as we have seen, Harrison understands the need to come through “to the other side” of such horrors and the final stanza does shakily re-establish the form (though the final line opens with two weak stresses and does not close). However, any naive understanding of the poet’s comments about coming through the fire can be firmly dismissed. This is not the place for any sentimental or rational synthetic solution. Simply, we are returned to the charred face whose painful, personal testament this poem has managed to encompass and movingly dramatise but without losing its form, thus ensuring a simultaneous sense of the universality of its art and message:

I went. I pressed REWIND and PLAY

and I heard the charred man say:

Part II

It was Wordsworth whose sense of physical rhythm in his verse was so powerful that he is reported to have often composed at a walk. It should come as no surprise that Harrison has been known to do the same. Though it was Keats’ ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ Harrison ‘mispronounced’ at school, it is actually Wordsworth who is more important to him because both share a belief in poetry as the voice of a man speaking to men. This conception of poetry as speech is a powerful constituent in Harrison’s work and perhaps one not clearly understood. John Lucas, for example, has attacked what he sees as loose metrics in the poem ‘V’ (7) but, to reverse Harrison’s comment that all his writing (theatrical or otherwise) is poetry, all his poetry needs to be read as essentially dramatic and deserves to be tested in the spoken voice as much as in the study. On occasions, Harrison, only half-humourously, draws attention to the fact that two uncles – one a stammerer, the other dumb – had considerable influence on his becoming a poet and it is the struggling into and with voice that such a claim highlights.(8) I have already mentioned Harrison’s interest in the curious idea that the true poet is born without a mouth. This too, implies the difficult battling for a voice or voices which can be found everywhere in his work and it is in this clamour that I find its dramatic quality. In a public poem like ‘A Cold Coming’, Harrison makes use of the contrasting and conflicting voices by playing them off against a regular form. This is almost always the case, but in what follows I prefer to concentrate less on metrical effects than on the way voices interweave, in this case, in more personal work from The School of Eloquence sequence.

The very title of the pair of sonnets, ‘Them & [uz]’, seems to promise conflict, at best dialogue, and it opens with what could be taken as the howl of inarticulacy. In fact each pair of these opening syllables gestures towards crucial worlds in Harrison’s universe. The αίαι of classical dramatic lament is echoed by the “ay, ay!” of the musical hall comedian cheekily working up an audience. Immediately, the reader is plunged into the unresolved drama of two differing voices, instantly implying the two cultures of the sonnets’ title. The line and a half which follows, sketching Demosthenes practicing eloquence on the beach, is intriguing in that its locus as speech is hard to pin down. It is perhaps intended at this stage (apart from introducing the poems’ central issue) to hover in an Olympian fashion above the ruck of dialogue that follows, implying the heroic stance which will be taken up in the second sonnet.

Line 3 opens again into a dramatic situation with the voice of the narrator (the adult Harrison), repeating his own interrupted recital of Keats in the classroom, while the master’s scornful comments appear fresh, unreported, as if still raw and present, in speech marks. The narratorial comment on this – “He was nicely spoken” – confirms this poem’s tendency to switch voices for its effects, this time its brief sarcasm barely obscuring the unironic comment likely to be made by an aspiring Loiner, or by an ambitious parent. The example of nice speaking given (again in direct quotes in the following line) is the master’s claim to possession, to authority in matters of language and culture and the separated-off reply of the narrator – “I played the Drunken Porter in Macbeth – with its full rhyme and sudden regular iambic pentameter, implies both a causal link between the two lines, painting Harrison as dispossessed specifically by the master’s attitudes, as well as conveying the tone of resignation in the young schoolboy.

It will be clear that much of the tension and success of the poem has already arisen from the dramatic interchange of voices and the master’s voice asserts itself again in line 7, ironically claiming a kind of monolithic, aristocratic purity to poetry which this poem has already attempted to subvert:

Poetry’s the speech of kings. You’re one of those

Shakespeare gives the comic bits to: prose!”

The following lines contain a curious wavering in the clear interplay of dramatic voices, only part of which is resolved as the poem proceeds. Evidently, the intrusive, even hectoring, parenthesis (at line 9) is the narrator’s questioning of what appears to be the master’s voice’s continuing argument that “All poetry” belongs to Received Pronunciation. Yet the aggression of this attack, with its harsh alliteration and sarcastic question mark, is out of key with the other narratorial comments in part I, though the tone is re-established in part II. In addition, I have some difficulty in accepting the master’s words as appropriate to the situation which – with no break – continues the speech made to the young Harrison. For example, the word “dubbed”, with its implication of the deliberate laying of a second voice over an ‘original’, already hands victory in the argument to Harrison’s claim for the authenticity of ‘dialect’ and, as such, would not be used by the believer in “the speech of kings”. Equally, the apparent plea, “please believe [Λs] / your speech is in the hands of the Receivers”, does not accord with the voice that summarily dismissed the pupil as a “barbarian” 7 lines earlier. In this case, Harrison’s desire for the dramatic has foundered momentarily on that old dramatist’s rock, the necessity for exposition which compromises the integrity of the speaking voice.

The true note of the master returns – interestingly, following one of Harrison’s moveable stanza breaks, as if confirming a shift in voice though the speech actually continues across the break – with “We say [Λs] not [uz], T.W.!” The tone of the responding voice, after the suggestion of a more spirited response in the Keats comment, has returned to the resignation of the brow-beaten pupil. This is reinforced by the more distant comparison of the boy to the ancient Greek of the opening lines, heroically “outshouting seas”, while the young Harrison’s mouth is “all stuffed with glottals, great / lumps to hawk up and spit out”. This first sonnet draws to a close with this tone of frustrated defeat for the boy, yet the drama has one final twist, as the voice of the master, sneering, precise and italicised, has the last word – “E-nun-ci-ate!“. There can be little doubt that the boy must have felt as his father is reported to have done in another sonnet from The School of Eloquence, “like some dull oaf”. (9)

The second part of ‘Them & [uz]’ contrasts dramatically with the first, though the seeds of it lie in the image of heroic Demosthenes and the accusatory tone of the reference to Keats which seemed a little out of place in part I. This second sonnet’s opening expletive aggression strikes a new tone of voice altogether. “So right, yer buggers, then! We’ll occupy / your lousy leasehold Poetry”. The poem’s premise is that it will redress the defeat suffered in part I in an assertive, unopposed manner. Not the master, nor any spokesman for RP is allowed a direct voice, yet the interchange of speech and implied situation can still be found to ensure a dramatic quality to the verse.

The passionate and confrontational situation of the opening challenge is clear enough, yet it’s striking how it has taken the autobiographical incident in part I and multiplied it (“yer buggers . . . We’ll occupy”) to present the wider political and cultural context as a future battlefield. Even so, there is no let up in the clamour of voices raised in the poem. Immediately, the narratorial voice shifts to a more reflective, past tense (at line 3) as the rebel reports actions already taken – and with some success, judging from the tone of pride and defiance: “[I] used my name and own voice: [uz] [uz] [uz]”. Even within this one line, the final three syllables are spat out in a vivid reenactment of Harrison’s defiant spoken self-assertion. It is this slippery elision of voice and situation which creates the undoubted excitement of these and many of Harrison’s poems as they try to draw the rapidity and short-hand nature of real speech, its miniature dramas and dramatisations into lyric poetry. A further shift can be found in lines 9 and 10, in that the voice now turns to address a different subject. The addressee is not immediately obvious as the staccato initials in the line are blurted out in what looks like a return to the situation and voice with which this sonnet opened. Only at the end of line 10 does it become clear that the addressee is the poet’s younger self, or the self created as the “dull oaf” by the kind of cultural repression practised by the schoolmaster. The reader is further drawn into the drama of the situation by this momentary uncertainty: RIP RP, RIP T.W. / “I’m Tony Harrison no longer you!”.

The remaining 6 lines are, as a speech act, more difficult to locate. There is an initial ambiguity in that they may continue to address “T.W.”, though the stanza break suggests a change and, anyway, this makes little sense as T.W. is now dead (“RIP T.W.”). In fact, these lines use the second person pronoun in the impersonal sense of ‘one’, addressing non-RP speakers in general, and it is the generalised nature of these lines which disarms the effectiveness of the passage. This is particularly important in line 14, “[uz] can be loving as well as funny”, the tone of which, commentators like John Haffenden have questioned. (10) The difficulty here is that if Harrison is addressing those who might use [uz] anyway, though there may well be many amongst them for whom the fact that “Wordsworth’s matter / water are full rhymes” is useful ammunition and reassurance, the same cannot be said of the “loving as well as funny” line which might be variously construed as patronising, sentimental or just plain unnecessary. Nevertheless, the poem regains a surer touch in the final lines in its use of the reported ‘voice’ of The Times in renaming the poet “Anthony“. The effect here is both humorous (this, after all the poet’s passionate efforts!) and yet ominous in that the bastions of cultural and linguistic power are recognised as stubborn, conservative forces, still intent on re-defining the poet according to their own agenda, imposing their own voice where there are many.

Harrison’s use of both metre and voice reflect the struggle in much of his work between the passion for articulation, especially of experiences capable of overwhelming verse of less conviction, and the demands of control which preserve the poet’s utterance as art. Harrison’s more recent work – especially that written in America – is more relaxed, meditative, less inhabited by differing and different voices, more easily contained in its forms. There are undoubtedly great successes amongst these (‘A Kumquat for John Keats’, ‘The Mother of the Muses’, part III of ‘Following Pine’) but there are moments when Harrison seems to idle within his technique, perhaps too able to ruminate aloud without the clamour of voices rising around him. It is likely that Harrison’s legacy will eventually be seen as a reassessment of the uses of formal verse and an exploration of the dramatic potential of lyric verse. These elements are rooted ultimately in his attempts to unite the rose of poetry with the weeds of truth and (often painful) experience, by trusting to the measures of his own body and to a language he returns to the mouth.

Footnotes

1. In a note to section III of ‘The White Queen’, Harrison records that “Hieronymus Fracastorius (1483-1553), the author of Syphilis, was born, as perhaps befits a true poet, without a mouth”. Selected Poems, p.30.

2. ‘The Inkwell of Dr. Agrippa’, reproduced in Tony Harrison: Critical Anthology, p.34.

3. See Richard Hoggart, ‘In Conversation with Tony Harrison’, Critical Anthology, p.40.

4. John Haffenden, ‘Interview with Tony Harrison’, Critical Anthology, p.236.

5. Hoggart, Critical Anthology, p.43.

6. The Gaze of the Gorgon, pp.48-54.

7. John Lucas, ‘Speaking for England?’, Critical Anthology, pp.359/60.

8. Selected Poems, p.111.

9. Selected Poems, p.155.

10. Haffenden, Critical Anthology, p.233.