We were out in Essex recently. My daughter is planning to get married and she wanted to look at wedding venues! I know. Things you do. I’ll give nothing away but just to say the trip was a success – the happy day will be in 18 months time. But while checking google maps as to how to get to the venue, I noticed that we were going to be driving near the village of High Laver. All sorts of bells clanged as a friend of mine used to rent a house up near there and we visited him many years ago. The house was a classic English cottage, must have been 16/17th century; nothing in it was straight, wood paneling everywhere, and he told stories of ghostly presences, things moving about in the night. I remember him opening an old wooden chest – something out of Wolf Hall, I now think – and inside was a fine old vinyl record player. Nice mix of old and new. The landscape was Essex-flat in the main, large fields. It must have been summertime – water irrigators were spraying the fields, and the fields seemed to be full of potato plants coming into flower.

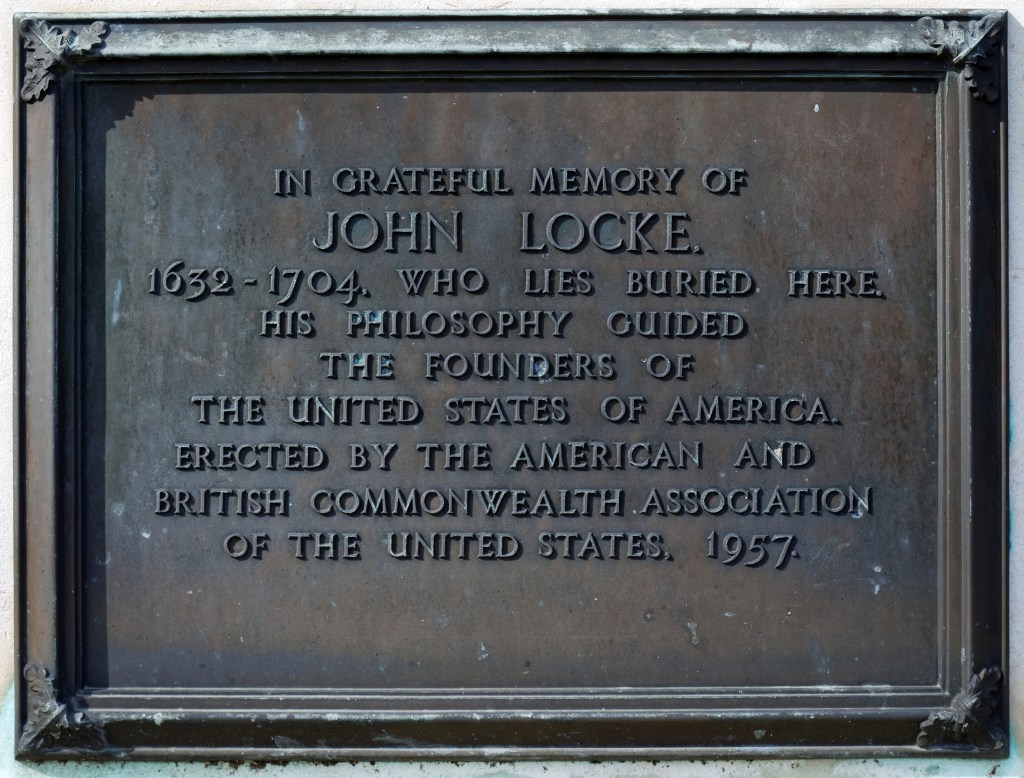

There was a party in the evening – of which I remember nothing – but at some point, we drove to High Laver itself, to All Saints’ Church. I imagine this was just a local ‘sight’, though it may well have been that I initiated the trip as I knew who was buried in the churchyard. Wikipedia tells me: High Laver is a village and civil parish in the Epping Forest district of the county of Essex, England. The parish is noted for its association with the philosopher John Locke. Yes – I may well have been fan-hunting an old philosopher’s grave. But this was not long after I’d completed my doctorate on the philosophy and poetry of PB Shelley and Locke’s influence on PBS formed a major chapter. Wiki again: one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the ‘father of liberalism’, Locke was one of the first of the British empiricists in the tradition of Francis Bacon. His ideas include social contract theory and significant contributions to epistemology and political philosophy.

The poem – a sequence of 5 short lyrics – that came from this visit was eventually published in my first book, Beneath Tremendous Rain (1990). I don’t remember the truth of the chronology, but the poem suggests I’d been to my parents’ home in Wiltshire, perhaps immediately before. Remember, I was coming out of years of Higher Education, probably wondering what (if anything) I was now fit for, ceasing (at last) being a child, becoming an adult, looking back and forwards into my own and my parents’ futures. So the ‘journey’ motif with which the poem opens is both literally geographical and autobiographical – the long summer roads of childhood…

I’ve beaten roads dusty with summer to be here.

Left the two of them, hands held, then waving

before the groomed hedge. Both looked older

again, walking Wiltshire fields, where slopes

have browned and stained poppy-red in places

like a bloody graze across sun-burned knees:

a hurt from those days quickly soothed by Mum;

bragged up later to a great exploit for Dad.

The two of them . . .

I remember I was pleased with the image of the Wiltshire fields (to be contrasted a bit later with the fields of Essex) and I know I was thinking/seeing in my mind a particular field beside the A4 from Silbury Hill to Marlborough on my regular route from Wiltshire to London: the dry field browning, the red poppies drifted through it: a graze on a sunburned knee. The drive to Essex goes on in the poem….

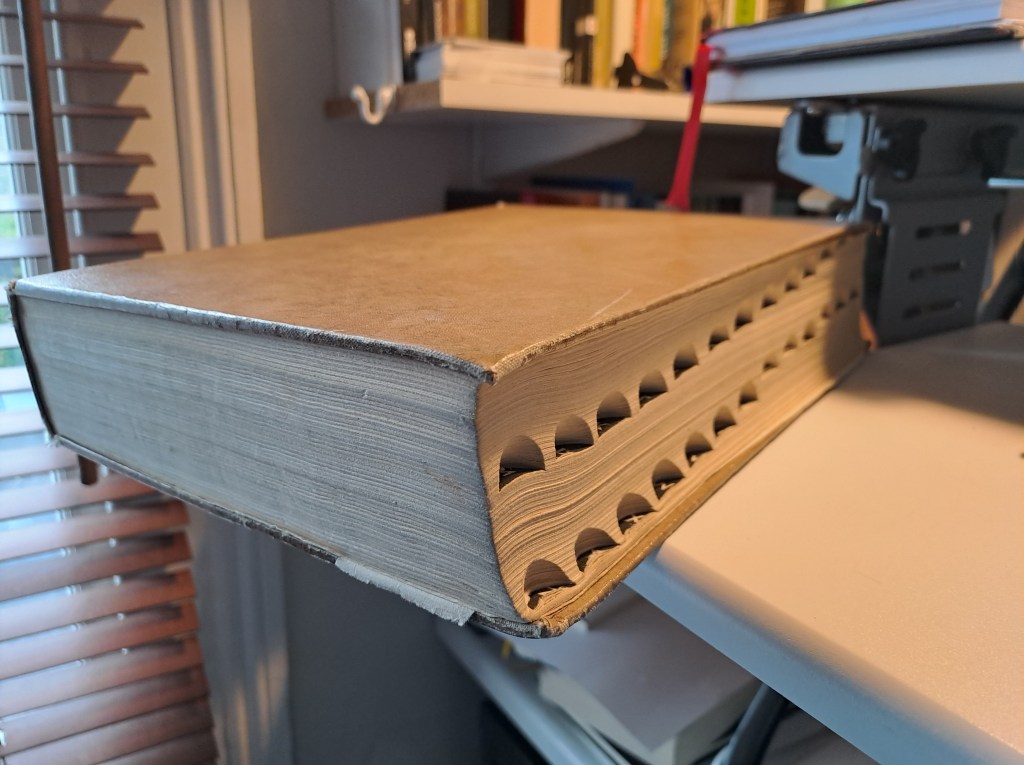

Absentminded,

my body alone has felt the pedals, held the wheel

as I’ve unearthed older and younger days

as precisely as those thumb-nail steps carved

in the solid encyclopedia I homeworked from,

perched at a desk on the edge of my bed.

The process of psychological recovery – the unearthing – of past youth: hence both ‘older and younger days’. As a schoolkid, I’d take homework upstairs, exactly as described here, unfold a little card table (green baize), sit on my bed, and work. The dictionary, I still have it. The Universal English Dictionary, edited by Henry Cecil Wyld, in the Thirteenth Impression of 1960. It smells musty, but still somehow of home. Is there a technical name for the thumb-nail steps for each letter of the alphabet? It is the precision of these steps and the idea of dictionary definitions that enter the poem here in the shape of my childhood and teenage faith in reason and empirical accuracy as a way forward (till I was 19 I thought I was going to be a scientist). The second part of the poem runs:

I bolted knowledge then.

The cuckoo, beak biggest part of itself.

A schoolboy stealing coinage from lucid books,

laying instalments on a life of smart logic.

The irony being applied to my younger self, my self-(over-)confidence, is a bit obvious I guess in the choice of ‘bolted’, the cuckoo image, the thieving image, ‘lucid’ and ‘smart’ as easy adjectives, and the hire purchase image of ‘instalments’. The contrast is made immediately in the poem via natural images of earth and stars (the potato flowers):

Now I drive through the fecundity of earth,

through these hectares of flowering potato,

white constellations adrift on undulating green,

with the conviction that this is a watershed:

x

so much of the talk at home is of death;

how do I brazen that out with an argument?

My old subject: time. Against which there can be no argument. What does the reasonable man say to time and death?

The third part of the poem re-states this same idea through a rather caricatured version of John Locke (the ‘stodgy book’ is his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689) which I’d waded through for my thesis). Time and death are restated also via images of the graveyard at High Laver, trying to make sense of my inclination to visit graveyards, finally accepting that the impetus for this is of the ‘heart’ not of the head.

I’ve come to where jet-sprays of irrigation

relieve the cracked fields of hot midsummer.

I’ve come in self-conscious homage to High Laver,

burial place of that logical father,

whose stodgy book of rational commonsense,

sprung the tradition I’ve clung to long enough.

x

A laburnum sapling creaks in its rubber thong

at a stake, where I stalk the graveyard to find

the oldest stone . . . Always I’ve done this,

yet surreptitiously, plotting false explanations

for myself as it’s the heart that says this

is a powerful place, where generations

of local good and ill in swathes

have gone down like centuries of grass.

In the fourth part of the poem, I am caught off-guard on what began as a ‘reasoned’ piece of literary tourism by an access of powerful emotion in relation to the lives and (feared) deaths of my own parents: ‘there’s more than I feared / of the two of them’.

But I forget what I’m here for.

Stood beside this body volume of displaced earth,

piled weeks ago beneath the trees –

on that last day some stranger’s beloved mother

had more flowers than she ever dreamed of.

x

The blown wreathes outstare me.

In a blink aside there’s more than I feared

of the two of them, wrapped against coming cold:

Dad, hands stuffed in his pockets,

standing off on his own; Mum, struggling

to peg out snapping shirtfuls of wind.

The sequence ends with more ‘straight’ description of the rural landscape of Essex. I remember labouring hard over the image of the water irrigation system which directs its spray (often 40 feet into the air) in one direction and then (through some mechanism I don’t know about) it flips and begins spraying in a quite different direction. I knew this was the ‘objective correlative’ of what felt like a significant shifting of my own outlook; simply, a recognition of the importance of the ‘heart’, though ‘judder’ ‘slam’ and ‘sudden’ suggest a near traumatic shift at that. Nor did I want the ending of the poem to be too gloomy, and those white-flowering potato plants return in the final phrase to suggest the psychic shift I’m trying to explore will have a fertility of its own (even if yet unseen) personally and artistically.

I watch the flailing mare’s-tail, the jet-stream

spray of the irrigator beside the church.

Its white angle above the potato fields

seems to crumple to a vaporous nothing, yet

a judder slams sudden clouds of fizzing spray.

It’s drenching some different sector of the field,

this drained, tearful, flowering place.