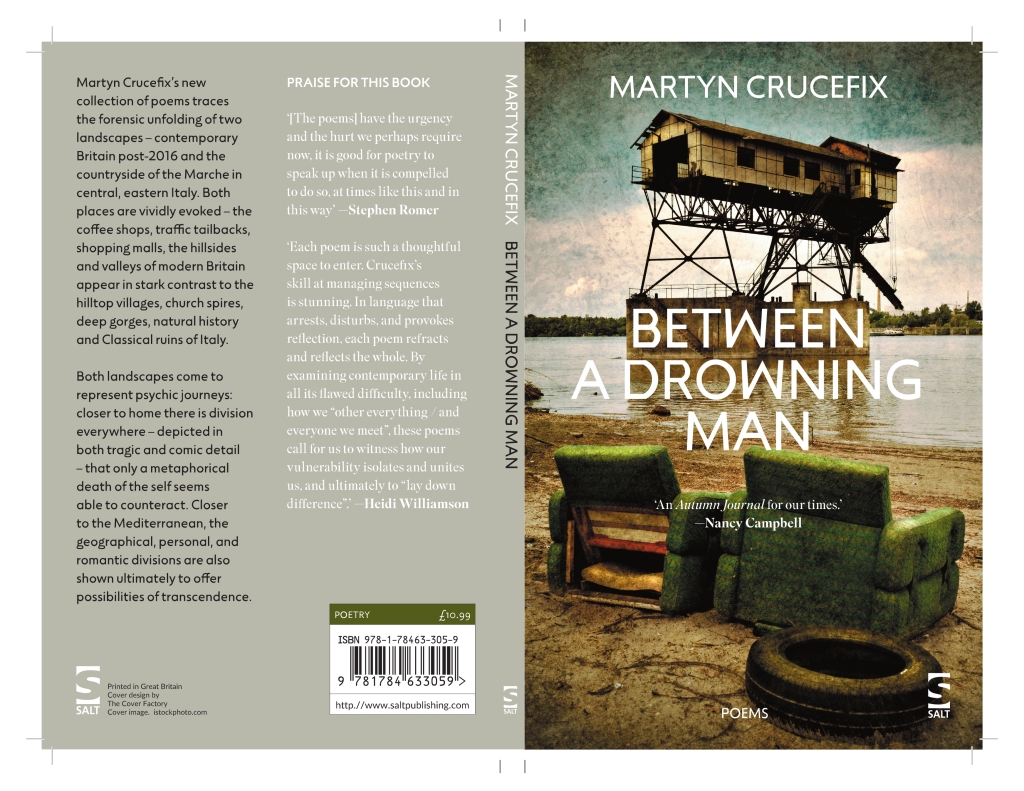

Available from Salt Publishing (Autumn 2023).

‘An ‘Autumn Journal’ for our times.’ —Nancy Campbell

‘Each poem is such a thoughtful space to enter. Crucefix’s skill at managing sequences is stunning. In language that arrests, disturbs, and provokes reflection, each poem refracts and reflects the whole. By examining contemporary life in all its flawed difficulty, including ‘how we other everything/ and everyone we meet’, these poems call for us to witness how our vulnerability isolates and unites us, and ultimately to ‘lay down difference’. —Heidi Williamson

‘[The poems] have the urgency and the hurt we perhaps require now, it is good for poetry to speak up when it is compelled to do so, at times like this and in this way’ —Stephen Romer

Listen to Martyn discussing the background and the writing of the poems in this new collection in these two podcasts:

Planet Poetry – about the whole collection

A Mouthful of Air – focusing on the single poem, ‘you are not in search of’ (page 57)

SOME REVIEWS OF THIS BOOK

By Mat Riches – on The High Window

By Stuart Henson – on London Grip

By Shanta Acharya – on Everybody’s Reviewing

BLURB OF THIS BOOK: Martyn Crucefix’s new collection of poems traces the forensic unfolding of two landscapes – contemporary Britain post-2016 and the countryside of the Marche in central, eastern Italy. Both places are vividly evoked – the coffee shops, traffic tailbacks, shopping malls, tourist-dotted hillsides and valleys of modern Britain appear in stark contrast to the hilltop villages, church spires, deep gorges, natural history and Classical ruins of Italy. Both landscapes come to represent psychic journeys: closer to home there is division everywhere – depicted in both tragic and comic detail – that only a metaphorical death of the self seems likely to counteract. Closer to the Mediterranean, the geographical and personal, or romantic, divisions are also shown ultimately to offer possibilities of transcendence.

The poems of the longer sequence, ‘Works and Days’, are startlingly free-wheeling, allusive – brilliantly deploying source materials and inspiration from Hesiod’s original and the 10/12th century Indian vacana poems – all bound together by the repeated refrain of bridges breaking down. The Italian poems, as a crown of sonnets, are more formally controlled, but the repeating of first and last lines of the individual poems likewise serves to suggest the presence of an overarching unity.

In the end, both sequences travel towards death which – while not denying the reality of human mortality, the passage of time – is intended to represent a challenge to the powerful dividing walls between Thee and Me, the liberation of empathetic feeling, even the Daoist erasure of the assumed gulf between self and not-self: ‘these millions of us aspiring to the condition / of ubiquitous dust on the fiery water’.