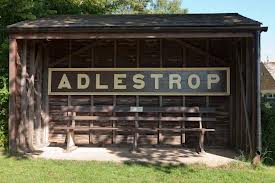

Having declared in my review of one year of blogging that I wanted to include more about teaching literature, I am posting some examples of the type of essay required by OCR exam board in module F661 (see also Essay 1). The essay following focuses on Edward Thomas’ poem ‘The Sun Used to Shine’ which can be read in full here. The poem has Thomas recalling happy days, walking with Robert Frost in the Gloucestershire countryside. Though the Great War had begun, neither of them had yet become entangled with it. Students are supposed to present a close analysis of one selected poem (AO2) while also putting that poem into relation with some others by Thomas (AO4).

Explore Thomas’ response to the English countryside of 1914 in the poem ‘The sun used to shine’. Your focus should be on close analysis of language, imagery, tone and form.

NB: Comparative sections here are in italics only to indicate the proportion of the essay devoted to that Objective (AO4). The main Objective remains AO2)

In this poem Thomas describes the English landscape as a place of pleasure and relaxed enjoyment as he walks with Robert Frost. These are remembered scenes and as the poem develops thoughts of the war of 1914-18 become more prominent. In the end perhaps the poem explores ideas about permanence and change, putting the war into a more historical perspective. The features which are typical of Thomas in the poem are the focus on the small details of the natural landscape (like ‘But These Things also’), the way the war lies in the background of the poem (like ‘Rain’ and ‘Tears’) and his interest in memory (‘Old Man’).

The opening stanza describes the two men walking at peace and the sun shining and here is an example of pathetic fallacy, the sun reflecting their happy mood. The easy rhythm of their walking is also reflected in the enjambement of lines 1-4 and the caesura in lines 2 and 4, giving a lilting, relaxed and flowing movement to the verse. At this early point in the poem, the regular ABAB rhyming adds to this impression and adverbs such as “slowly” and “cheerfully” obviously reinforce this sense of easy pleasure. The phrase “sometimes mused, sometimes talked” also suggests their free and easy life, with the caesura here again giving the steady walking rhythm of the opening as they contentedly (but thoughtfully – “mused”) explore the English landscape. This is similar to ‘As the Teams’ Head Brass’ where Thomas uses enjambement in many of the opening lines to reflect the flowing movement of the horse and plough up and down the fields. In that poem there is even less punctuation, reinforcing the idea that in ‘The Sun Used…’ the caesuras’ reflect the stopping and starting of the two men’s walking pace.

The narrator’s statement that the two men “never disagreed” about which gate to lean on is probably hyperbolic but again suggests their closeness and harmony and even the action of leaning on the gate with no urgency or hurry reflects their relaxed state of mind. From line 6 the narrator conveys their mental focus as they walk through the landscape and suggests that they are wholly occupied in the enjoyment of the present moment. The phrases “to be” and “late past” suggest both past and future to which they give “small heed”. Other subjects are suggested by the phrase “men or poetry” and the “or” here suggests their easy freedom even in topics of conversation. However, it is at the end of stanza 2 that the war is first mentioned though at this point the word “rumours” is used, suggesting that the subject is only vaguely picked up and this is reinforced by the use of the adjective “remote” which is placed at the end of line 9 giving it an particular emphasis. At this point the war is not an important element as they walk through the landscape and this is also suggested by the word “Only” at the start of line 10 which rather dismisses the war topic of conversation in place of their focus on the landscape, this time in the form of the apples they find there.

The description of the apples is ambivalent because they are initially described with the adjectives “yellow” and “flavorous” suggesting their attractiveness and sweet taste so the reader may be a bit taken aback to hear in the next line that wasps have “undermined” the skin of the apples. The most important thing about this latter word is that it suggests the mines and mining associated with the battlefields of World War One and therefore suggests that thoughts of the war even penetrate the pleasant walks through the countryside of the two men. Something like this can also be seen in ‘Rain’ in which the narrator listens to rainfall in a depressed mood and hopes that no one who he “once loved” is doing the same. That poem uses a natural image of “Myriads of broken reeds all still and stiff” which also can be interpreted as referring to the many dead on the battlefields of France. ‘The Sun Used…’ was actually written in 1916 when Thomas was about to join up though the memory of the walks refers to 1914 when the war did seem further from him personally. These suggestions of war are continued in stanza 4 with the line of betonies described as both “dark” in colour (a contrast to the yellow apples?) and with the metaphor of “a sentry”. This makes very explicit the war reference and this is continued with the description of the crocuses (their “Pale purple” suggesting both weak vulnerability and shade) as having their birth in “sunless Hades fields”. Each of the words in this phrase might suggest the war with the darkness of “sunless”, the reference to death in “Hades” (the Classical land of the dead) and “fields” which surely refers to the battlefields in France.

These suggestions that thoughts of war cannot be excluded from pleasant walks in the English countryside in 1914 are confirmed with the very next line: “The war / Comes back to mind”. Here it is the rising moon that reminds the two men of the war as they remember that the same moon would also be visible to soldiers on the battlefields of France “in the east”. The next word “afar” again suggests the distance of the war, though actually the poem has suggested that thoughts of it are not at all remote. The narrator’s thoughts now go beyond thoughts of the 1914 war. Typical of Thomas, he develops a more historical perspective, referring to earlier wars, “the Crusades / Or Caesar’s battles”. This has an ambiguous effect as it might suggest some consolation that war has always occurred and perhaps always will. On the other hand, perhaps it suggests the more depressing thought that humankind cannot avoid warfare. This sense of long stretches of time is quite common in Thomas’ work such as in ‘Aspens’ where he describes the trees at the crossroads and there implies that they are permanent, even indifferent to the human world: “it would be the same were no house near. / Over all sorts of weather, men, and times”.

Perhaps it is this longer historical perspective that creates the thoughts of the final 11 lines of this poem. They open with a hyperbolic statement that “Everything” fades away and Thomas then uses a series of similes of things which he regards as transient, starting with the “rumours” of war, running water vividly described as “glittering // Under the moonlight” and the two men’s “walks” through the English countryside, even the men themselves (in line 26) and the apples from stanza 3 (now more pessimistically described with the adjective “fallen”) and the men’s “talks and silences”. This is a very inclusive list which gives the impression of time sweeping away many of the pleasures of life. The climax of the list is the last simile that seems to wipe away memories too (an important element in many of Thomas’ poems). He seems to suggest that memories are like marks on sand and the tide washes them away (is the tide an image of Time?). The poem ends with images of “other men” enjoying the same “easy hours” that the poem began with though now Thomas and Frost have vanished. In these last lines some things have changed (“other flowers”) but the moon alone remains “the same” suggesting that much of the landscape even will have changed (this reminds me of the felled elm tree in ‘As the Team’s Head Brass’ in which the English landscape is shown to be changing).

In this poem, Thomas records pleasures gained from walking in the English countryside in 1914 though he also suggests that thoughts of the war cannot be excluded. As the poem goes on, it seems to become detached from the countryside but does return to it at the end in suggesting that though people may vanish and die and even aspects of the countryside itself may change in the long perspectives of Time, there are a few things – like the moon – can be seen to remain constant.