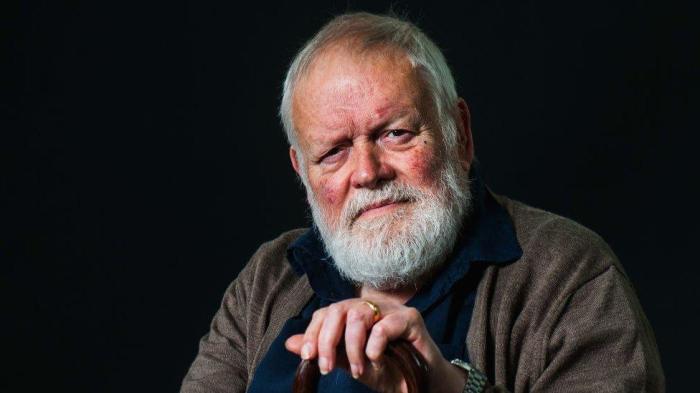

Social media – at least the bit of it that arrives on my screens – is alive this morning with many expressions of sadness at the announcement of the death of Michael Longley. I heard him read just a few months ago to launch his most recent new selected poems, Ash Keys, at the LRB Bookshop in London. He insisted then on trying to stand to read his poems, though his breathlessness and physical wobbling often made him have to take his seat again; but the humour and mischievous twinkle were as powerful as ever. Over the years, I have to admit it took me a while to really come to appreciate his work; I think I did not really ‘get’ the force of his brevity, his precision. If you have not seen it yet, do watch the brilliant, moving, inspiring BBC programme about him, his life and work here. I’m posting below my review of his 2014 collection, The Stairwell (the review originally published in Poetry London) and I hope it manages to say something useful to both new and older readers of this wonderful poet. Here he is reading ‘Remembering Carrigskeewaun’ on The Poetry Archive.

Keeper, custodian, traditionalist whose work is stringent, formalist, always elegant: critical judgments on Michael Longley’s work fence him round too closely, running the risk of misleading, even discouraging, new readers. It’s true, as a member of Philip Hobsbaum’s Group in Belfast in the 1960s, Longley’s poems were criticized for their elegance of form, rhetorical grace and verbal eloquence, though he found something of a kindred spirit in Derek Mahon. Longley wrote poems that were “polished, metrical and rhymed; oblique rather than head-on; imagistic and symbolic rather than rawly factual; rhetorical rather than documentary” (The Honest Ulsterman, November, 1976). But Seamus Heaney’s different aesthetic was Hobsbaum’s star turn and quickly became a national, then international preference. Attitudes solidified around Longley although (perhaps in the cause of self-definition) this was not something he resisted, casting himself and Mahon in the 1973 poem ‘Letters’ as “poetic conservatives”.

‘Epithalamium’, the poem that since 1969 has opened Longley’s selections and collecteds reinforces the caricature and in ‘Emily Dickinson’ he sees the need to dress “with care for the act of poetry”. But Longley’s long standing admiration of Edward Thomas was not for nothing and he shared a desire to dismiss Swinburnian “musical jargon that [. . . ] is not and never could be speech” so that in The Echo Gate (1979) he is experimenting, on the one hand with the plainly Frostian ‘Mayo Monologues’, and on the other with short, imagistic pieces in which the authorial voice seems to have taken a vow of non-intervention. ‘Thaw’ reads, in its entirety:

Snow curls into the coalhouse, flecks the coal.

We burn the snow as well in bad weather

As though to spring-clean that darkening hole.

The thaw’s a blackbird with one white feather.

This is a mode that Longley has continued to explore in accordance with another (surprisingly) early statement of poetic intent. The poet’s duty is to “celebrate life in all its aspects, to commemorate normal human activities. Art is itself a normal human activity. The more normal it appears in the eyes of the artist and his audience, the more potent a force it becomes” (Longley, ed. Causeway: The Arts in Ulster, 1971).

Subsequent collections have become concerned to list, to name, as it were ‘merely’ to record experience for its own sake, often in vivid short poems which run the risk of seeming inconsequence, though Longley has never lost his unerring eye and ear for the poetic line. Nor has he ever seriously questioned the adequacy of language (within conventional bounds) to represent experience. It’s in these ways that his work is conservative but his poems’ intention to encompass and witness is far more radical. To witness – whether it is the song of a wren near Longley’s beloved Carrigskeewaun, a Belfast bombing, or the camp at Terezin – is to acknowledge that we are bound together by what happens. From Gorse Fires (1991) to The Weather in Japan (2000) Longley comes to sound like Eliot’s Tereisias who, as the pages turn, has “seen and foresuffered all”. The beauty of nature, the horrors of mankind, birth and death, the present and the distant past are all absorbed into his steady gaze, a steady voice, intent on an anatomy of connection.

One such connection is the way Longley has been re-visiting the Iliad and Odyssey for years now, producing vivid, contemporary accounts of key scenes. Priam’s visit to Achilles tent in Book 24 of the Iliad famously became Longley’s poem ‘Ceasefire’, appearing in The Irish Times in 1994 when the IRA were considering a ceasefire themselves. The poem forges links and connections between enemies and across millennia. As ‘All of these people’ puts it, “the opposite of war / Is not so much peace as civilization” and civilization needs to be founded on a right relationship with even the smallest of things. Among many poems that articulate an ars poetica, ‘The Waterfall’ envisages the best place to read his own collected works as “this half-hearted waterfall / That allows each pebbly basin its separate say”. It is such civilized allowance, rather than the much-vaunted preservation of a tradition, that is the mark of Longley’s aesthetic, moral and political outlook.

His new collection, The Stairwell, is much obsessed with death though its inevitable reality has already been embraced by the poet’s allowance. An Exploded View (1973) already contained ‘Three Posthumous Pieces’ and twenty years later, ‘Detour’ mapped out his own funeral procession. Here, Longley has been “thinking about the music for my funeral” (‘The Stairwell’) and much of the book has the feeling of an ageing figure readying to depart. Longley himself refers to his “unassuming nunc dimittis” (‘Birth-Bed’) and the only ceremonial he anticipates is to be provided by robins, wrens, blackbirds: “I’ll leave the window open for my soul-birds” (‘Deathbed’). The counterweight to civilized allowance, even in the approach of death, is modesty and humility. If gifts are to be handed on to the future then they ought to include a little poem about a wren: “Its cotton-wool soul, / Wire skeleton [. . . ] / Its tumultuous / Aria in C” (‘Another Wren’).

Such unassuming gifts to future generations are balanced, in the civilized society Longley seeks out, by the commemoration of the past. This is something his poems continue to do with his re-imagining of his father’s experiences in the Great War and this new collection contains more of these poems; his father at ‘High Wood’ among “unburied dead”, befriending the future Hollywood star, Ronald Colman, or taking an ironic “breather before Passchendaele” (‘Second Lieutenant Tooke’). Whether looking forwards or backwards, the true gift lies in the specific, not the generalized. ‘Insomnia’ recalls Helen Thomas calming and consoling the mad Ivor Gurney, by guiding his “lonely finger down the lanes” of her husband’s map of Gloucestershire. Longley looks for this too. Here is the whole of ‘Wild Raspberries’:

Following the ponies’ hoof-prints

And your own muddy track, I find

Sweet pink nipples, wild raspberries,

A surprise among the brambles.

Having translated a poem by Mikhail Lermontov, Longley goes on to wonder what his “understated” neighbours around Carrigskeewaun would make of such “grandiloquence” (‘After Mikhail Lermontov’). It’s in the avoidance of a hyper-inflated language and tone that Longley’s re-makings of Homer are so good. The new book contains a fair sampling of these too, many of them in the second half which forms an extended elegy, commemorating Longley’s twin brother, Peter. The Homeric paralleling works less well in this context, though the unrhymed double sonnet, ‘The Apparition’, in which the ghost of Patroclus pleads to be buried by Achilles, addressing him as his “dear brother” is powerful. But I’m reminded of Heaney’s Station Island (1984) in which he revised and regretted his earlier use of “the lovely blinds of the Purgatorio” in writing a poem about the murder of Colum McCartney in Field Work (1979). Longley’s Homeric material casts such a strong shadow and the vital life of Peter is insufficiently conveyed, except in a few recollections of their shared childhood, tree-climbing, bows and arrows, boxing, visiting the zoo. Nevertheless, Longley’s determination to commemorate his twin, with whom he shared “our gloomy womb-tangle” (‘The Feet’), re-confirms human closeness, allowance, the giving of space to others, to nature, is what has driven this poet’s work for more than forty years.

![flowermoonPNG[1]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/flowermoonpng1.png)

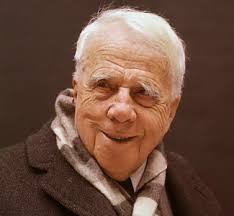

Frost wants to make big claims for metaphorical thinking: “I have wanted in late years to go further and further in making metaphor the whole of thinking”. He allows the exception of “mathematical thinking” but wants all other knowledge, including “scientific thinking” to be brought within the bounds of metaphor. He suggests the Greeks’ foundational thought about the world, the “All”, was fundamentally metaphorical in nature, especially Pythagoras’ concept of the nature of things as comparable to number: “Number of what? Number of feet, pounds and seconds”. This is the basis for a scientific, empirical (measurable) view of the world and hence “has held and held” in the shape of our still-predominating scientific view of it.

Frost wants to make big claims for metaphorical thinking: “I have wanted in late years to go further and further in making metaphor the whole of thinking”. He allows the exception of “mathematical thinking” but wants all other knowledge, including “scientific thinking” to be brought within the bounds of metaphor. He suggests the Greeks’ foundational thought about the world, the “All”, was fundamentally metaphorical in nature, especially Pythagoras’ concept of the nature of things as comparable to number: “Number of what? Number of feet, pounds and seconds”. This is the basis for a scientific, empirical (measurable) view of the world and hence “has held and held” in the shape of our still-predominating scientific view of it.

That we have a tendency to forget this provisional nature of knowledge and understanding seems to be Frost’s next point. We take up arms (as it were) by taking up certain metaphorical ideas and making totems of them. He berates Freudianism’s focus on “mental health” as an example of how “the devil can quote Scripture, which simply means that the good words you have lying around the devil can use for his purposes as well as anybody else”. That this is dangerous (makes us not safe) is illustrated by the passage of dialogue Frost now gives between himself and somebody else. The other argues that the universe is like a machine but Frost (adopting a sort of Socratic interrogation technique) draws out the limits of the metaphor, concluding he “wanted to go just that far with that metaphor and no further. And so do we all. All metaphor breaks down somewhere. That is the beauty of it. It is touch and go with the metaphor, and until you have lived with it long enough you don’t know when it is going. You don’t know how much you can get out of it and when it will cease to yield. It is a very living thing. It is as life itself”.

That we have a tendency to forget this provisional nature of knowledge and understanding seems to be Frost’s next point. We take up arms (as it were) by taking up certain metaphorical ideas and making totems of them. He berates Freudianism’s focus on “mental health” as an example of how “the devil can quote Scripture, which simply means that the good words you have lying around the devil can use for his purposes as well as anybody else”. That this is dangerous (makes us not safe) is illustrated by the passage of dialogue Frost now gives between himself and somebody else. The other argues that the universe is like a machine but Frost (adopting a sort of Socratic interrogation technique) draws out the limits of the metaphor, concluding he “wanted to go just that far with that metaphor and no further. And so do we all. All metaphor breaks down somewhere. That is the beauty of it. It is touch and go with the metaphor, and until you have lived with it long enough you don’t know when it is going. You don’t know how much you can get out of it and when it will cease to yield. It is a very living thing. It is as life itself”.