I’m shocked to realise that it is a full year since I posted my review of the stunning long poem, Porcelain, by the contemporary German poet, Durs Grünbein, in Karen Leeder’s equally impressive translation (Seagull Books, 2020). That review was originally commissioned for, and published in, Patricia McCarthy’s penultimate issue of Agenda (those who follow such things will know that Patricia has handed over the reins of the magazine to John Burnside who takes over with the resources of St Andrews behind him). In its original incarnation, the review was paired with my comments on another contemporary German poet’s work (again in Karen Leeder’s translation): this was Ulrike Almut Sandig’s 2016 collection, I Am a Field Full of Rapeseed, Give Cover to Deer and Shine Like Thirteen Oil Paintings Laid One on Top of the Other (Seagull, 2020). I am now posting my Sandig review as well, in part because I will be appearing with both Karen and Ulrike at the Ledbury Poetry Festival in a few days time. We will be talking about Rainer Maria Rilke’s great sequence, Duino Elegies (1923) as part of Peter Florence’s Dead Poets Society series. If you are in or around Ledbury on the morning of Saturday July 7th, do come along. Here’s the review . . .

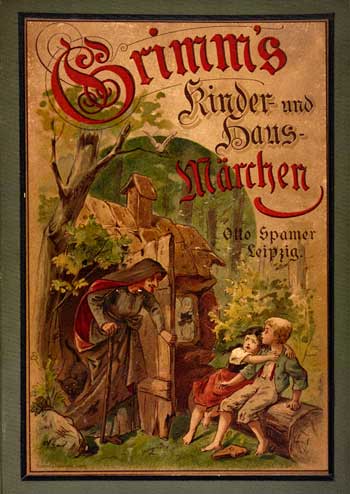

The eponymous figure from Grünbein’s sequence’s 11th poem,‘Hans im Glück’, draws on one of the stories in The Children’s and Household Tales of the Brothers Grimm (1812). In the original, Hans has anything of value taken from him, bit by bit, yet he remains optimistic, refusing to acknowledge reality. Within the context of Porcelain, Grunbein treats this is as an additional image of the myth of the city of Dresden as undeserving victim. Interestingly, the same figure appears in Ulrike Almut Sandig’s collection, but her presentation of Hans is more poignant, less ironic, as even the boy’s language is stripped from him and he tries to write a letter to a loved one: “what are you up to? // + esp: where r u? / ru ru // ru”. In the context of I Am a Field Full of Rapeseed… , the boy might be thought of as a refugee, forcibly having his culture and language stripped from him, though one of the strengths of the poem is that it also works as an updated fairy tale, a little myth of loss and diminished presence with more universal application. Such re-purposing of several of Grimm’s tales is one of the most striking things about this collection. Sandig announces in another poem, “we find ourselves deep in the future of fairy tale” (‘the sweet porridge’) and she, like Angela Carter before her, redeploys the fairy tale’s surreal narratives, bold characterisation, its humour and violence, its symbolism and moral intensity for her own purposes.

The other striking aspect of Sandig’s writing here is her bold linguistic and formal choices. There is an absence of punctuation, capitalisation, of poem titles (bolded phrases mid-poem often serve as titles), of conventional forms, of a clear lyric ‘I’, of plainly pursued narratives. This results in radically shifting ground for the reader which can be both bewildering and exciting. Several poems indicate these choices are firmly rooted in issues of epistemology and ideas concerning personal identity. So, the opening poem, ‘from the wings’, ambitiously sets out a complete life from ‘screaming’ beginning to its ‘silent’ conclusion. The interim is portrayed as all fluidity, ‘a stream that flows into others / while others again flow into it’. As much as there is any discrete self to be identified, ‘I am made wholly of language’, and the individual is a creature ‘that must speak / to understand itself’. The self is also one of many ‘fragile / greedy alpha-creatures’ and understands itself to be, ultimately, ‘a fluid tuning fork I am my own / song’. In the same vein, the book closes with ‘where I am now’, which sets the self metaphorically in some remote Arctic research station, a self that is at the same time a woman swimming in a municipal pool, moving freestyle through the water, ‘parting the water before me’, in an image of self-creation and open-ended exploration that, to some, will recall Eliot’s ‘Little Gidding’: “We shall not cease from exploration”.

This is, as it were, the metaphysical background to Sandig’s vision and it gives rise to poems like ‘I am the shadow for you to hide beneath’ in which the narrative voice celebrates just such fluidity of identity in an address to “friends”/readers that has the quality of Whitman’s “I contain multitudes” (Song of Myself, #51), though with a good deal more anxiety: “every morning I get up and don’t have a clue: / is it me, Almut? Ulrike?” This is also the poem containing the book’s full title, “I am a field full of rapeseed, give cover to deer / and shine like thirteen oil paintings laid one on top / of the other” and the poem goes on, in the name of radical fluidity, the I as landscape, huntress, a text that begins to unravel just as it reaches an end, a soldier, a girl, a woman. Elsewhere, ‘to be wood in a table’, as the title suggests, continues the theme: “not to be old and not to be young, but old / enough to be several things at once”. This includes the Rilkean desire for “simple things like ‘tree’” as well as the freedom of having no name, “no longer to say: ‘I am’”.

Such poems are both celebratory in tone, but also alertly defensive. The reason is that there are forces abroad, ways of seeing and their associated politics that offer counter narratives. So, the expected calm of ‘lullaby for all those’ is really a call to arms, or at least a call to resist. It is “for all / those who put up a fight, when somebody / says: lights out, no more talking”. In a superb passage, once again Leeder’s translation of the German is brilliant, the forces of “DARKNESS” begin to emerge by implication:

we’re waiting for two

or three of those good, humming dreams

four peace treaties, five apples in deep sleep

we are waiting for six cathedrals and for

those seven fat cows, eight quiet hours

full of sleep, we’re waiting for nine friends

gone missing. we’re counting our fingers.

x

we’re still resisting. we won’t go to sleep.

What is being resisted are the forces of repression, of fixity not fluidity, narrowness not breadth, fundamentalist conviction not open-endedness. Sandig places a poem in the centre of the book which draws heavily on statements made by Pegida, Germany’s populist, right wing, anti-immigration party. The text is full of rallying calls expressing a faith in clarity, mastery, resolution and purification: ‘from now on / nothing will stand in our way, no language / we cannot master, we will strike out mistakes / and shake each other’s freshly washed hands”. One of the Grimm’s sourced poems, a sister speaking to her brother, presents a narrative of the boy’s development into a threatening “hunter”. Such a poem looks both ways towards the violence of neo-Nazis, but also towards the violent radicalisation of young jihadists.

Sandig’s poems dealing more obviously with issues of state power, war, migration and displacement (especially hot topics in Germany, a country in the Schengen area of Europe and seen by some as an ideal destination – see the poem ‘tale of the land of milk and honey’) are particularly impressive. The ‘ballad of the abolition of night’ draws on details of systematic torture prosecuted by the USA, “a state lagging somewhat behind / on the historical timeline of our kind”. ‘instructions for flying’ revises statements made in leaflets distributed at the Idomeni refugee camp in 2016. The same camp, close to the borders of Greece, is the focus of another poem which expresses the poet’s “moral dismay”. The disquiet is partly at her own nation’s equivocations about the refugee crisis (what if there’s not a single / jot of good Deutsch to be found in this / Land of mine”) but also personally, at finding rhymes but ultimately doing “sweet FA”.

With Grunbein, Sandig is expressing the moral complexity in the face of man’s inhumanity to man as much as any simplistic moral dismay. This is, in part, the subject of some of the Grimm poems (interestingly, in German, the word ‘grimm’ means ‘anger, ire’). ‘Grimm’ itself opens optimistically, messages being scribbled onto raw eggs, but increasing urgency leads to extra pressure and the eggs break. Still, like Hans in luck, the narrator seems “unfazed in / the crumbling ruins” though the final image is only of eggs smashed, “a well-nigh limitless / supply of fragments and rage most grim”. But Sandig is an optimist, I think. Though couched in conditionals, ‘news from the German language, 2026AD’ works hard to portray a future of more settled diversity (Iraqi dates, Turkish honey, Syrian poetry). The opposing prospect is relegated to a parenthesis – if quite a long one. But hope has the final word: “if it works, we, that’s all of you and me, / will sing a lullaby, rhyme in unison [. . .] but more than that, we will be”.