An edited (shorter) version of this review first appeared in Poetry Salzberg Review in June 2025. Many thanks to the editor, Wolfgang Görtschacher, for commissioning the writing of it.

It is as a poet writing in Gaelic that MacNeacail – who died in 2022 – is most well-known, though he would himself provide translations of his work into English, what, in the poem ‘last night’, he refers to as Gaelic’s ‘sister tongue’. There were also poems written in Scots and these variants give an insight into what Colin Bramwell here calls ‘the language situation in Scotland’ within which MacNeacail worked all his life. For a number of years, MacNeacail lived and wrote under the anglicised name Angus Nicolson, but always considered himself a tri-lingualist and antagonistic to the kind of divisiveness such a ‘situation’ might give rise to. His natural inclination was democratic, pacifist, anti-authoritarian, and modernist. Now, the collection, beyond (eds. Colin Bramwell with Gerda Stevenson (Shearsman Books, 2024)) gives readers a selection of poems written in English by Aonghas MacNeacail over the past 30 years. One of the implications of the book’s title is his deeply held wish to look ‘beyond’ division, not to anything transcendental (MacNeacail’s focus was always this world, not some other), but to the next term in an on-going dialectical process. One of the little gems from ‘the notebook’, included here, imagines a cup of knowledge, the liquor within, also knowledge, a grain is added and stirred, and the grain then consumes the liquor and continues to ‘grow, root, sprout / find elbows, crack the cup // find clay’.

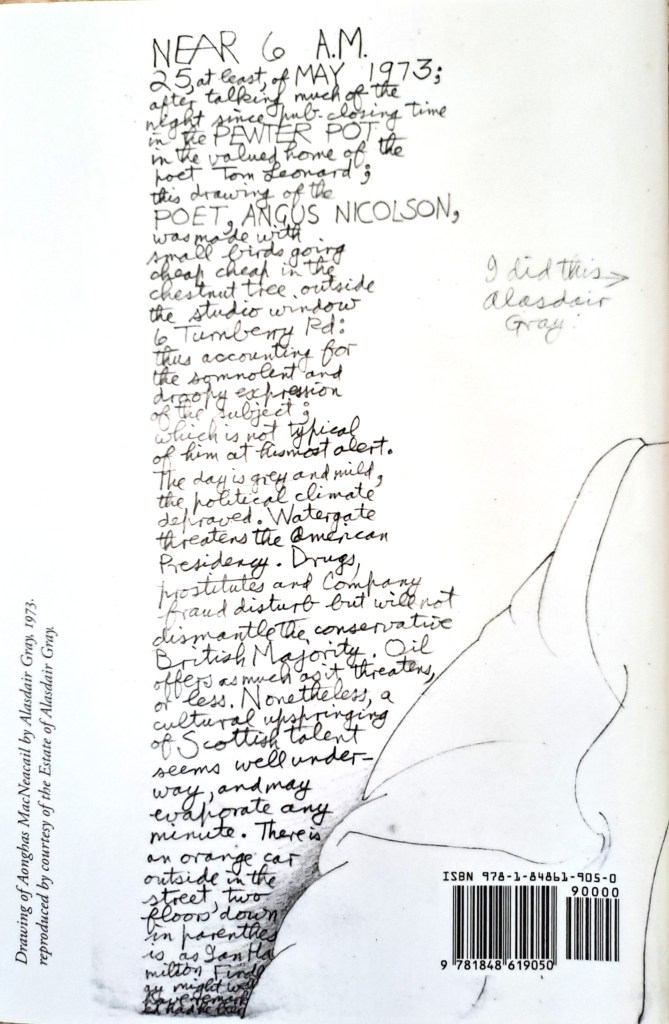

MacNeacail’s modernism took its key lessons from the likes of William Carlos Williams, Olson, and Creeley and most of the poems here have that fluid, unpunctuated (hence pointed by the breath), often short lined, often indented formal shape we associate with the Black Mountain. He was a member of one of Phillip Hobsbaum’s fertile ‘groups’ (along with Liz Lochhead, Alasdair Gray and Tom Leonard) and the advice given was to go back to his roots, to ‘write about what you know’. In part, this took MacNeacail back to his childhood, growing up in Uig, on the Isle of Skye, speaking only Gaelic. It also made it clear what he wanted to escape from: Gerda Stevenson describes this as ‘the confines of the proscriptive Free Church of Scotland’. Several childhood poems, illustrate the stifling force of religion, on his mother, for example, ‘strapped down tightly / by a darkly warding book thick with orders that drove / and hedged her way’ (‘missing’). The church governed education too, the teacher little more than a ‘stern presence’, who demanded ‘psalms / from memory’ (‘crofter, not’).

The teacher’s ‘granite eye’ also features in ‘forbidden fruit’ where the contrast is between education’s confining ‘barbed-wire’ and the invitations of the natural world (of Skye), specifically the allure of ‘the biggest [. . .] sweetest’ nut hanging on a branch over a waterfall. The poem ‘had adam not eaten the apple’ feels like a later piece, with a more self-confident, liberated MacNeacail declaring ‘the thing is / not to always / spell the word correctly’ and imagining god’s demands for eternal perfection leading him to waken every morning, complaining ‘another fucking immaculate day’. A longer poem like ‘gaudy jane’ gives a sense of MacNeacail’s unshackling from restrictions. The figure addressed is part woman, part a realm of liberation, a window onto ‘wild excursions’, towards ‘dancing voices, laughing feet’, she is a glass of whisky, a doorway into nature, to sensuality, and a way to access the ‘little gods of mischief and delight’. Celebrations of the natural landscapes of Skye (and elsewhere) in fact become one of the characteristics of MacNeacail’s writing. Snowfall over hills is as if ‘god’s apron / settles on our field and makes / a tranquil bowl’ (‘snowhere’). In ‘a rainbow’, the natural phenomenon is enjoyed and admired, ‘so real // high up on that pentland slope’, its natural beauty preferred to any fanciful talk of pots of gold, its fleetingness an image of imagination and memory. MacNeacail’s ‘primula scottica at yesnaby’ celebrates the rare wildflower’s fragile beauty, its hardy nature, till it also becomes an image of Scotland itself: ‘the air it breathes is stiff with brine / this whit of life still flowers / every tiny purple radiance is lambent / in the blood of time’.

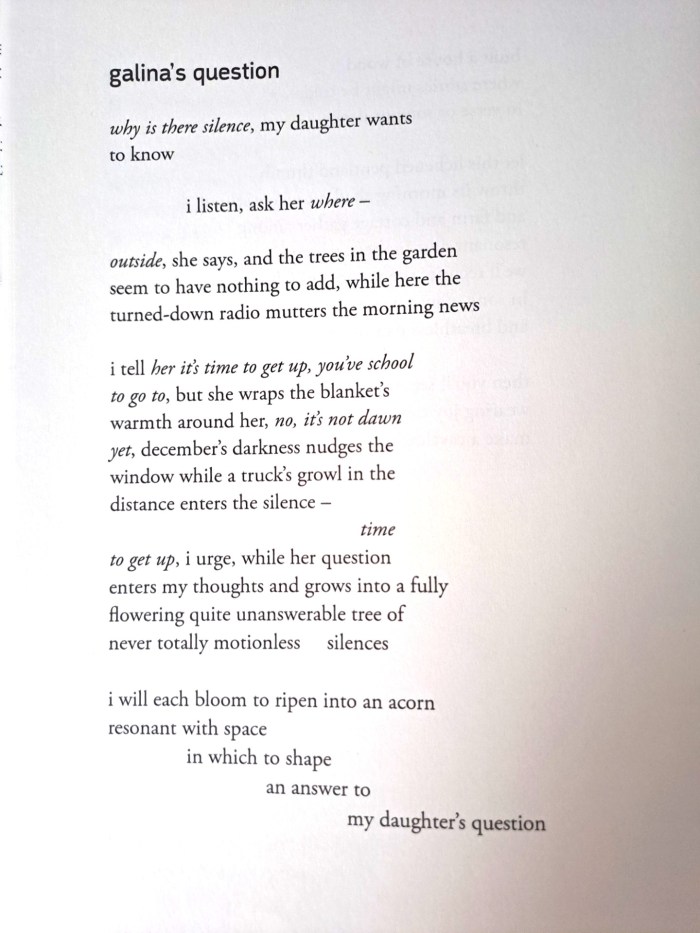

MacNeacail’s love of Nature is matched only by his writing on the varieties of human love, erotic, romantic, filial, parental, between friends. I can’t think of any other poet who’d compose 80 lines (both touching and hilarious) in praise of ‘some of my best friends’. A poem like ‘love in the moonlight’ is unashamedly romantic in its contrasting of the moon’s ‘pallor’ with the loved one’s ‘sun- / wrapped noons, bright mornings / and the way your evenings / dance into a fiery dusk’. There are several delicate poems featuring MacNeacail’s daughter, Galina, and – reminiscent of Courbet’s ‘The Origin of the World’ painting – ‘the curious eternal’ is a marvellous erotically-charged paean to a loved one, ‘after all those years / the mystery / of flesh, secretions, pulse and breathing patterns’. MacNeacail’s English poems exude a human warmth that, to judge from comments from friends and colleagues, was true to the man himself. They are driven by his wish to communicate – in whatever language, in truth – and his slipping free from Christianity’s ‘one book’, that would ‘consign all art and ingenuity / to black irrelevance’ (‘this land is your land’), allowed him to celebrate the flawed, the not perfectly straight, the interrupted conversations, that constitute being human with a passion and modesty. These lines from ‘the notebook’, are a characteristic, and invaluable, vade mecum: ‘no matter / how little / you say / it may / be worth / the saying, if it / touches the edge / of a shadow / that can / (possibly) / be thinned / by the breath / of words’.