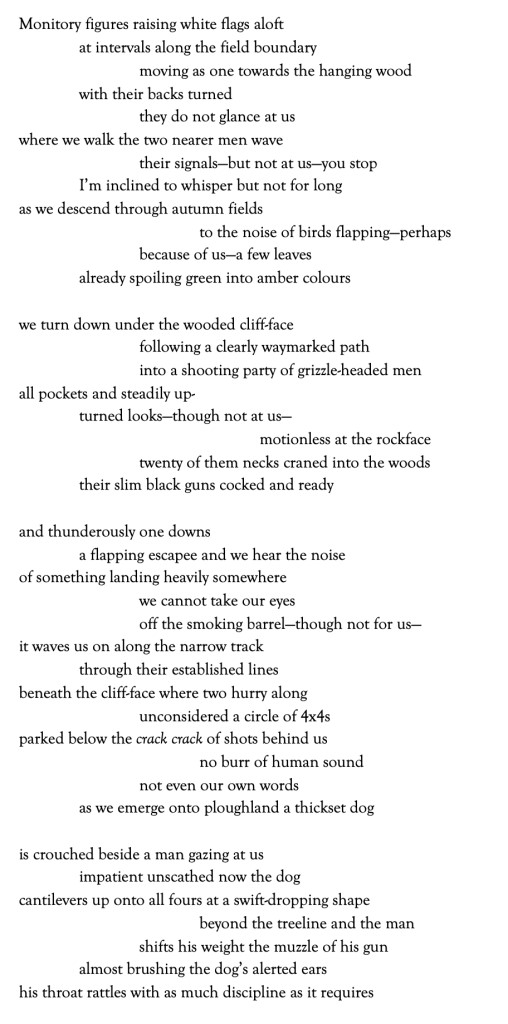

Happy New Year to all of you. We are hoping for the best aren’t we? Come rain, shine or named storm, the poems go on, saying something at least for the individual, the social, for careful consideration of the world out there, the world in here, and the languages we use. I’m posting a poem which has just appeared on New Year’s Day at the excellent Modron Magazine, its strap line is ‘Writing on Nature and the Ecological Crisis’. Glyn F Edwards also interviewed me about the making of the poem and I’ll post the text of that below, along with the link to Modron. Do go and take a good look at what other work they have put up in this new Issue 5. And then subscribe to them. My poem is weirdly formatted – so here is an image of it, lacking its title which is: ‘Muzzle’

On the Writing of ‘Muzzle’

MC: It’s so interesting to be encouraged to look back at the process of writing a poem. I seldom do it (I suspect I’m not alone), forever rushing on to the next ‘best’ thing (we think, we hope). In looking back at ‘Muzzle’ (I find I have the very first draft and several subsequent ones) two things strike me: that it took so long to get to a ‘finish’, and that I’d forgotten how important the context of the poem was to what it might be expressing.

The first draft was scribbled in a notebook in the autumn of 2016. Earlier in the same notebook, I was sketching out thoughts on my, then, just-published version of the classic Chinese poems, the Daodejing (Enitharmon, 2016), preparing for readings I was to give from the book. Elsewhere there are fragments about my parents’ growing difficulties at home and (later) in their care home, plus some quite late drafts of the longish poem about the plight of refugees in the Mediterranean which was published as Cargo of Limbs (Hercules, 2019), and even first drafts of the poems which have eventually come to make up my most recent collection, Between a Drowning Man (Salt, 2023). Remember, the Brexit referendum took place in June 2016 and if there is an idea that links all these differing creative endeavours (including ‘Muzzle’) it is the idea of ‘division’.

Q1 – Only with the word ‘dog’ at the end of the third stanza does the reader gain a semantic connection to the ‘Muzzle’ in the title of the poem. Of course, Chekhov’s gun was ‘cocked’ all along, and the ‘muzzle’ becomes the open end of a weapon where a bullet escapes. Can you explain a little more of the rationale for this subtle title?

MC: To my surprise, I find, the first draft has no ‘muzzle’ mentioned in it at all. But the shape and a lot of the substance of the finished poem is already there: the flag-waving men during an idyllic autumn walk (on the Sussex Downs, as far as I remember), the shooting party, even the man and his dog at the end of the poem. The muzzle of a ‘smoking gun’ is clearly implied but the final dog’s muzzle does not make an appearance till quite late (I mean 2020 or so!). In fact, in the first draft I clearly don’t know how to end the poem. There, the walking couple emerge from the wood ‘unscathed’, the dog in the field grows tense, and there’s a sense of the man’s day being ‘interrupted’ by the couple. But these final 5 lines are crossed through. In the later draft, the dog now ‘cantilevers up’ onto all fours (the mechanisation of the creature is part of the male group’s malign influence in my mind) – but still no muzzle as such. That only comes via a reference to the man’s gun and, with its proximity to the dog’s head and ears, there is a transference of the word/idea to the dog itself. I’m pretty sure it wasn’t till this point that I thought of calling the poem ‘Muzzle’ and that I also wanted the word to apply to the walking couple who have been (by the experience, by their apprehension, if not their genuine fear) muted or muzzled themselves. The idea was actually there early on; the first draft briefly sketched in, ‘no human voice we do not talk’.

Q2 – The refrain ‘not at us’ is repeated, and echoes again in ‘not for us’ – amongst the ‘white flags’, and the reassurances of safety, there appears a growing threat to the speaker. The reader is left with the feeling that somehow this danger extends beyond the shooting party, and beyond bloodsports. Did you seek for the poem to act as a wider allegorical foreboding, and, if so, would you elaborate on the metaphor?

MC: Yes, the ‘not at us’ phrase or versions of it are already in the first draft, indeed on four occasions. This is one of the main sources of the idea of ‘division’ in the poem. It’s a simple ‘us’ and ‘them’ situation. The white flags – I think these would simply be the shooting-party’s beaters’ flags being waved to move the birds across the field into the woods, or possibly they are genuinely ‘monitory’ (meaning simply to warn or admonish), but in being white they also have (ironic) resonances of surrender (these guys were not going to surrender anything). The repeating phrase emphasises the gulf between the two elements of the encounter and particularly the sense (clear on the actual occasion) that those holding guns did not seem much concerned that unsuspecting, endangered walkers might be near at hand. We felt ignored; they seemed not to look at us. Being England, there is a strong class element here, which does not map easily onto the question of the voting intentions by class in the Brexit referendum, but factions on all sides seemed not to be paying much attention to any other. The devastating Tory defeat of 2024 should be regarded as reflecting much of this: eventually the country at large felt those in government were simply not paying any attention ‘to us’. I’ve always been pleased with the adjective ‘established’ to describe the shooting-party’s positioning, their being arrayed as the ‘establishment’. The finished poem ends ambivalently. The walking couple escape the shooting-party but are faced with another threatening situation: the gun, the dog. The ‘guard-like’ posture now puts me in mind of prison camp patrols the world over and I’d be happy for readers to get there too: there is a policing of freedoms going on here, a sliding scale from rural pastimes, to political enforcement, to genocidal pograms.

Q3 – ‘Muzzle’ zigzags, indents, retraces its steps. Some stanzas loop longer, and when the final sestet ends abruptly, without full stop, the reader becomes aware of the absence of punctuation throughout. You have a very idiosyncratic approach to presenting and punctuating the poem – could you share your intentions in this poem, and elaborate on whether these ally or counter your conventional style?

MC: The final form of the poem – which you describe so well – came very late. Most often my poems ‘find’ their own form – they don’t begin with any sense of the shape they will eventually take. The 2020 draft was coming out in tercets and I remember liking the ‘walking pace’, step by step, which that shape suggested. But in the end I wanted the poem to be more radical, to suggest a sense of freedom (in contrast to what is felt by the couple during the incident), a freedom to roam as it were, for lines to wander across the page and back again, while also acknowledging that this meandering might well yield some uneasiness in the reader (where’s he going?!). Both freedom and anxiety would be appropriate here. The form and the absence of punctuation (the latter I have been working with for several years now) are intended to generate some ambiguity. For example, I’m hoping for a fluidity in the opening lines, with the putative subject or focus being the flag-waving men, eliding to the walking couple – the ‘you’, then the ‘I’ – the birds, the leaves turning, finally to the ‘grizzle-headed men’. Within this fluency, a bit later, I want several adjectives to be hovering between subjects. The word ‘unconsidered’ floats between the lack of consideration given to the couple and the waiting circle of parked cars. Similarly, ‘impatient unscathed’ buzzes between the couple (again) and the waiting man and dog. This culminates in the rattling throat in the final line which (I want) to be as much about the man as the dog itself and so the ‘discipline’ demanded of the situation ought to be seen as human as much as canine. I guess I’m trying for fertile ambiguities, trying to suggest two things at once. The opening of the Daodejing says: ‘the path I can put a name to / cannot take me the whole way’ (my version).

Q4 – The shooting party negatively influences their surroundings, their presence ‘Hanging’ and ‘spoiling’ the woods, and the walk of the speaker. How much familiarity do you have with these ‘grizzle-headed men’, and do any occasions, such as the one in ‘Muzzle’ stand out as memorable, or significant?

MC: As you suggest, I have allowed the shooting-party to be, and remain, those wearing the black hats. More often than not I feel the need, the wish, to revisit such emphatic designations: what’s to be said ‘on the other hand’ (ever the wishy-washy liberal). The jaw-dropping presumption of the shooters in the original incident (the poem says pretty much exactly what happened), coupled with the generally felt anger and dividedness of the UK at the time (and since) goes to explain why I have not done so here. Do I know people like this? I guess not. A remote acquaintance likes to share his stories of attending such exciting shooting-parties, but it’s hard even to find the language to create much common ground. Perhaps I am just too urban, metropolitan even. About hunting wild animals, Rilke says, ‘to kill is one form of our restless grief’ (Sonnets to Orpheus, II, 11; my translation). Nothing I witnessed on that day in 2016 served to convince me otherwise; the taking out of another living thing for no useful purpose seems to require an arrogant presumption that I cannot get my head around and I find rather terrifying; the ‘monitory’ urgency in the final poem is as much concerned with how this sort of attitude plays out in the political, even in the military, sphere as it is with ‘blood sports’ more narrowly defined.

December 2024

Here’s the direct link to Modron – https://modronmagazine.com/a-poem-and-interview-with-martin-crucefix/

![moulin-glacier-11[2]](https://martyncrucefix.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/moulin-glacier-112.jpg)