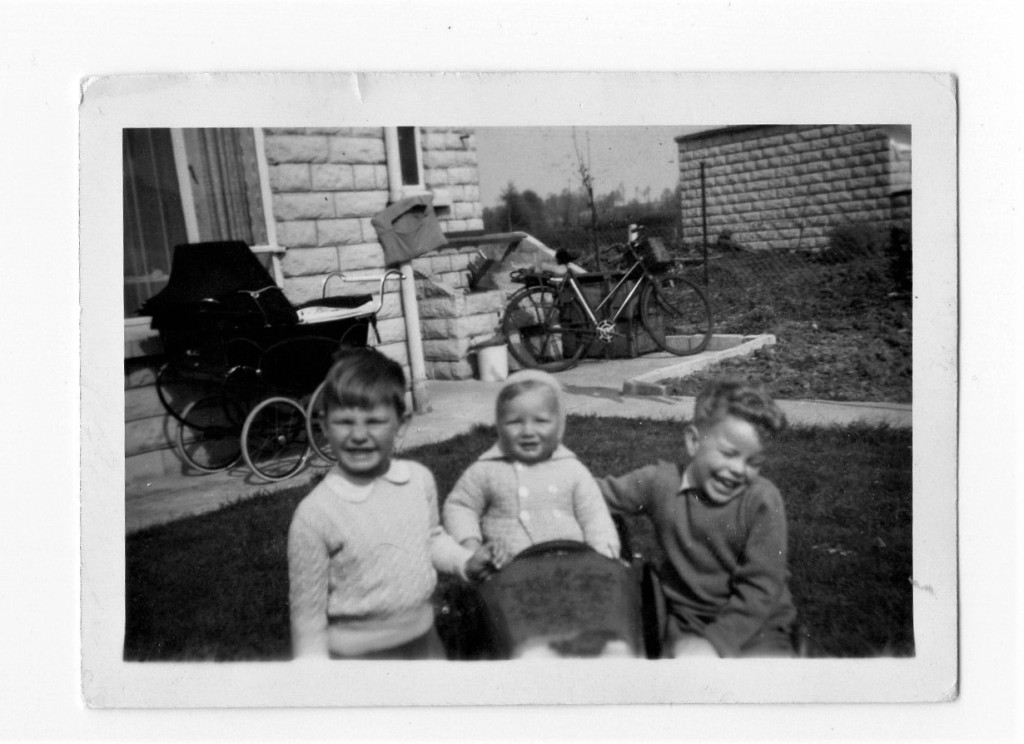

On any criteria, it is a poor photograph. The primary subject – the three young boys in the foreground – are out of focus. The youngest one’s head is just too low for the dated camera’s pre-set focus to find it. Instead, there in the background, but far more sharply defined, is a woman’s bicycle, the chain ring and two slanting elements of the metal frame reflecting the sun brightly. I know the orientation of this house. If the sun is falling this way, the time must be nearing mid-afternoon, the sun is falling on the garden and over back of the house, over the photographer’s right shoulder, into the eyes of the children, each of whom is squinting slightly. Look beneath the large pram under the window, to the left: the shadows of its four spoked wheels and their pale tyres confirm the angle. The black bulk of the pram and the mass of shadow behind and beneath it almost take over the image. It too is in sharper focus than the children.

Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida suggests our viewing of a photographic image has two aspects. What he termed the studium is associated with any viewer’s knowledge and cultural experience, with a body of information and a general interest: ‘a very wide field of unconcerned desire, of various interest, of inconsequential taste’ (tr. Richard Howard, Vintage Books). It is a mere question of liking, not liking. Here, the studium of the image is open to anyone with a decent knowledge of England in the mid-20th century. The corner of a recently built house (the garden as yet untended, only wire fencing between this and the next house on what looks like a raw housing estate) and the style of bicycle and pram, the clothes the three boys are wearing (what look like home-knitted jumpers – the youngest wrapped up with a knitted hat, buttoning under the chin – so the weather is not warm) are all suggestive of the late 1950s or early 1960s. The youngest boy is also sat in a toy pedal vehicle – the long-nosed bonnet indicative of a racing car – the sun’s angle perhaps catching brightly again what might be headlights at the very bottom of the image.

The outline of this lawn in the back garden remained unchanged throughout my childhood. Its corner – in the image, its apex – falls neatly behind the youngest boy’s head. Perhaps there is some composition here? I’d guess it was my father pressing the white button on the black plastic box of a Kodak camera. Taking such a picture was more the father’s job in those days. His clumsiness in framing the image ought not to be judged too harshly (these were still relatively early days for mass photography) but it stirs in me the thought that he was always a man more at home with objects than words or people. I wish he’d taken the picture again, a little lower, filling the chosen frame with his three children. Forty years later, setting the scene behind the large window in the image, sat around the dining table that (for fully 50 years) looked out onto the back garden, I wrote of him when forgetfulness and confusion troubled him more and more:

Past ninety and still no books to read

your knuckles rap the laid table

x

gestures beside a stumble of words

so much aware of their inadequacy

x

it hurts us both in different ways

since a man without language is no man

x

finding too late the absence of words

builds a prison you’re no longer able

x

to dominate objects as once you did

the world turns in your loosening grip

So, it may be the general studium of this image stirs some mild interest in you – the period, the clothes, the main objects a little like museum pieces. Barthes’ second element in a viewer’s response to a photo, he termed the punctum, some detail (usually only one) that pierces the viewer, that wounds us, a powerful emotional response. The punctum is often not intended by the photographer – some random detail that for a particular viewer has a disproportionate and very personal impact. It is what moves us.

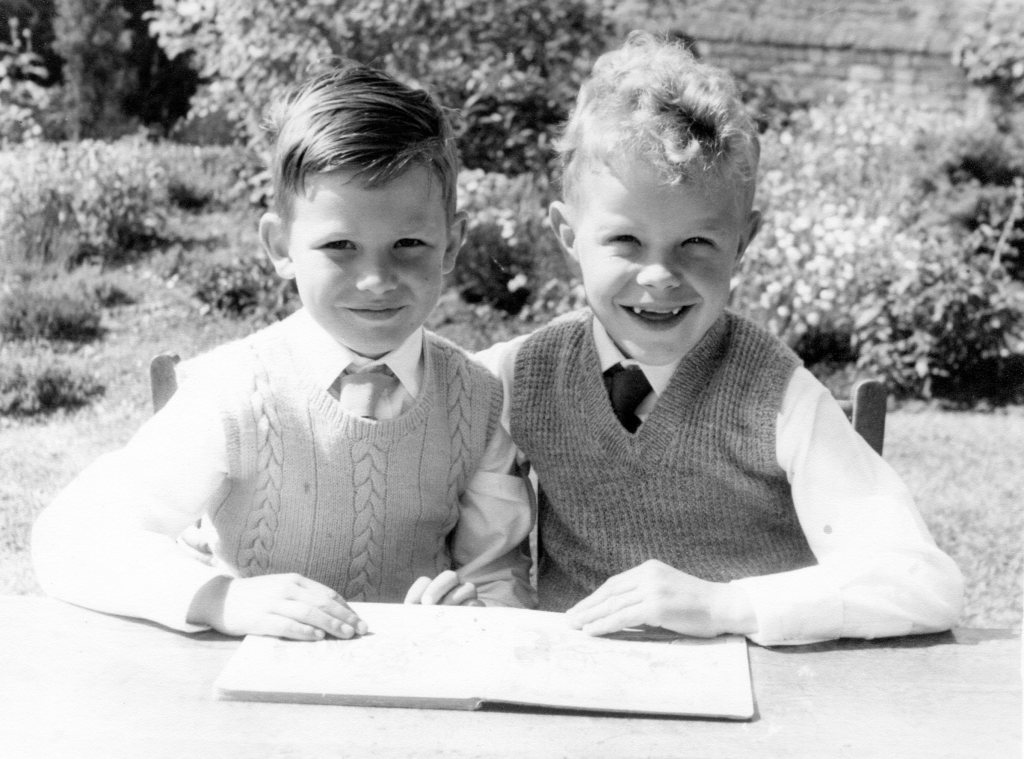

The fact that this is an image from my own past means there are a number of candidates here for a punctum. Most likely surely is the face of the boy on the left. Under a thick head of hair, a rough-cut fringe, he squints more than the others. His eyes cannot be seen, hidden away in the dark slits beneath the eyebrows. The firm lines on his face slant down from nose to half-opened mouth in a grin that lifts his cheekbones, that might even be the shaping of a word. The long vowel in the word ‘cheese’ perhaps? A version of that face greets me in the mirror even now. In these infant and junior years, my jumpers were knitted by my mother. I seem to be wearing a girlish collar beneath. My right hand is lost beyond the lower edge of the image. My right rests on the racing car, not quite clasping my younger brother’s hand which looks set back a little on the edge of the car. I am the middle child. My younger brother must be little more than a year or two old (born in 1959). My older brother is the one full of animation: right arm around the car, around his little brother, he seems to be exploding into a fit of giggles. But oddly, none of these details quite wounds me…

The bicycle? My mother’s of course. A large wicker basket on the front. Look closely and there on the back is the folding child’s seat I remember sitting in as she pedaled the 2 or 3 miles into town. The vast contraption of the black pram? I don’t have memories of it – even of my brother in it. It remains part of the studium – I remember later discussions about the way pram and child would be left outside for hours on end (sometimes in the front garden of the house where the sun’s absence kept it cool in summer). I think a general thought: such a thing would never be countenanced these days. Even far older children are seldom let out of their parents’ sight.

The house itself? A little tugging of nostalgia here (we eventually sold the house after my parents’ deaths just a few years ago) but mostly I sense information welling up. An estate of 40 such houses on the edge of a Wiltshire town. One of the first ever post-war self-build projects – the 40 men built them with their own hands over 3-4 years in the mid- to late-50s. I have other photos of the house being built. Each dwelling had a little outhouse (ours is middle top of the image; next door’s filling the top right corner). There’s a non-standard coal bunker: it’s what Mum’s bike is propped against. If I remember rightly my paternal grandfather helped build it. I have a vague physical memory of being held by him (over the bunker?). Nothing more, since he died suddenly, I think, before this image was taken.

Oddly – and this is in the nature of the Barthsian punctum – the detail that has particular poignancy (like a dagger, Barthes says) is the shapeless peg bag hanging (where it always hung, it hung there forever) on the bracket attaching the guttering downpipe to the wall. The camera simply records what lies before it. After 100 pages of discussion, Barthes arrives at, what even he confesses is, a less-than-earth-shattering conclusion that a photo’s potency lies in its declaration of ‘this-has-been’, its evidential power. Yet it’s also the case that an image’s power can be contained in what is absent from it or is implied by small details within it. I am pierced by the peg bag because it represents (more than that – it is, it manifests, the touch of) my mother. The only member of the family nowhere here (neither behind nor in front of the lens), she is there in her bicycle, there in the pram (possibly there in the waste bin beside the coal bunker – has it just been washed out? there is a darkening patch of water running on the path?). But most of all in the peg bag. Almost certainly she made it herself. A coat hanger. A few lengths of spare cloth. Some wooden pegs. The washing line ran down the length of the back garden path. There was a long wooden prop with a V cut in the top. In a very early poem, I would see her ‘struggling / to peg out snapping shirtfuls of wind’.

In Susan Sontag’s On Photography, she writes ‘[w]hen we are afraid, we shoot’. She means when we fear losing what-is-here we preserve it in the museum of the recorded image. Did my father fear losing this moment? He preserved it badly. But he managed to preserve the children (though the ones in this image are now passed on into something quite other; Barthes would say they have died). Nowadays, a father would turn his camera and include himself in it too. What does that say about fear? The peg bag would still be hanging there though. In the image. On my desk here. Scanned to the screen. In my mind, the peg bag continues to hang in its place on the downpipe though other people’s children play on the lawn, other parents sit gazing out of (what we always called) the dining room’s picture window.

this was such a marvellous read – I used to have Barthes’ book but failed to finish it (despite the economy of its pages) somehow it got lost in a house move so am very grateful for your summation of it here, tied to that frozen moment of this very personal and pertinent photo

” a stumble of words” – memorable!

p.s. the housebuilding project was unknown to me but it surely makes the house even more personal

LikeLike

Really like this Martyn. I remember our peg bag too. Have a lovely christmas and all power to your elbow for 2022. Karen

Karen Leeder, FRSA, MAE Professor of Modern German Literature, Fellow and Tutor in German New College Oxford OX1 3BN

‘Mediating Modern Poetry’: mmp.mml@ox.ac.uk

See my translation of Durs Grünbein,’The Doctrine of Photography’, in Poetry https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/144808/the-doctrine-of-photography

New College ® is a Registered Charity – No. 1142701 & Trade Mark – No. 2588652. ________________________________

LikeLike

Thank you Martyn for your summary of Barthes writing on photography-it came at an ideal time, and thanks for the ecard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Martyn, a really thoughtful and relatable take on Camera Lucida.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lovely piece, and unexpectedly moving. Thanks, Martyn

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a beautiful & inspiring piece.

‘since a man without language is no man

finding too late the absence of words

builds a prison’

The stumble of words, the peg bag, the evidence of the mother through the domestic, the garden plot.

Thanks

LikeLike

Many thanks Jane (am just completing that little job you gave me – good luck with that in the New Year)

LikeLike

As you say just one photo can really stir the memory banks, it’s good to see your Dad smiling, he looked really happy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good to hear from you Bruce – I find I dwell a bit more on the past than I used to – a sure sign of age but not necessarily a bad thing in itself. Hope you and all yours are doing OK

LikeLike

Just re-visiting this excellent article again Martyn ahead of doing my Punctum workshop at Suffolk Poetry Festival. I’ve done it a few times ahead of you writing this. Camera Lucida played a big part in my thinking when writing Whistle my first collection, and is still always there with me. Thanks again for this. I hope you don’t mind, I’ve sent it ahead of me to the participants as pre-reading – it’ll allow us to get down to business so much quicker and better equipped & also save them form listening to at least some of my blathering. All the best Martin

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Martin – apologies as I’ve just picked this up… So I trust the workshop went swimmingly. Thanks for noting this blog post and for sending it it even further on its way. Quite happy for such things to be used elsewhere – I take it as a sign of its life and vitality (and have not yet succumbed to prtectionism or profit-making). I catch updates on yourself and helen on FB of course. You are both so impressively busy. Best of luck to you both – and helen as I think she’s launching soon? with warmest wishes

LikeLike

Thanks Martyn, it worked really well – sending it out first saves the participants from my waffle and we can get into it, much quicker. We do give the impression of busy quite well! About to watch the Ilya Kaminsky lecture, so better go.

LikeLiked by 1 person