A rather more personal post than usual, though a poem (an older one of my own) is attached to it. Last week, I spent a few days with family in the beautiful village of Blockley, in the Cotswolds. The weather was very good for late November and we walked a couple of times – from Broadway up the muddy hill to the folly of Broadway Tower (once frequented by William Morris apparently) and around Hailes Abbey (now a ruin, local lore has it that Thomas Cromwell watched the destruction of the Abbey from a nearby hilltop). Blockley itself is near Moreton-in-Marsh, a place almost destroyed by the volume of traffic flowing through it (even in November), where The Bell Inn was once a favourite of JRR Tolkein, and is supposedly the model for The Prancing Pony in The Lord of the Rings. But Blockley, for me at least, had another powerful ghost haunting it.

As a couple, with young children, we stayed in the village over 20 years ago, in one of the original silk weavers cottages built along Park Road, which looks down over the village and valley. The house was owned by a colleague of mine at the time, Laurence Bowkett. He taught Classics and Latin and often spent the summer vacations away on archaeological digs of various kinds. That must have been the situation then as he’d allowed us to use the house in his absence. His early death, within a year or two of this, was a shock to us all. He had no family of his own and I don’t know what happened to the house later. So, fast forward to 2024, and here we are staying in Blockley again, only partly by coincidence. We have always had good memories of the place and (again, partly by an AirB&B chance) we ended up renting an almost identical cottage in the very same terrace above the village. Indeed, maybe it was the same cottage – I couldn’t remember enough of the details. The layout was certainly the same – the front door in off the road, straight into a little front room, a chilly basement kitchen and upstairs two small bedrooms.

Laurence’s was not the first death of a contemporary I knew well, but it greatly affected me and I tried to express something of this in the poem – an elegy – I wrote for him later. It is called ‘The umbrella and the bay tree’ and it mixes memories of him, his enthusiasms (he had a lot of those – all his students loved him for it), with details from my own family life at the time. It opens with an imagined scene, all his teaching colleagues gathered (as we often did then) in the local pub, remembering him in his absence. The ‘laral gods’ – the Lares – are Classical Roman guardian deities. The laurus nobilis refers to a little bay tree I bought after our first stay in Blockley as a thank you gift . . .

x

By seven-thirty, you are with us all

tonight in the gloom of The Washington,

though we omit you from every round.

Powerless as laral gods who gave you

no protection, even laurus nobilis,

x

the bay tree I bought you, proved no use.

x

Our children were at Infant and Junior School at the time and – to be honest – I can’t now remember if the details the poem goes on to mention are truth or fiction. But Laurence was the kind of guy who’d keep his own books in scrupulous order (as he did with his extensive collection of Marvel comics) so the library setting has always felt right . . .

x

Today, I searched 570 and 790,

in the Dewey decimal classification

your fingers ran through a thousand times,

for the facts of death and irrepressible life,

x

as if I looked for you now and you then.

You taught shard-life and careful fieldwork,

the near-dead language of not giving in.

You offered the heroic a modern face,

though death proved the more determined.

x

You understood lives alter what they touch:

a house, a street, a flowering tree,

for those who know us are not struck dumb,

a library unread the moment we die.

They roar like a lantern with our life inside.

x

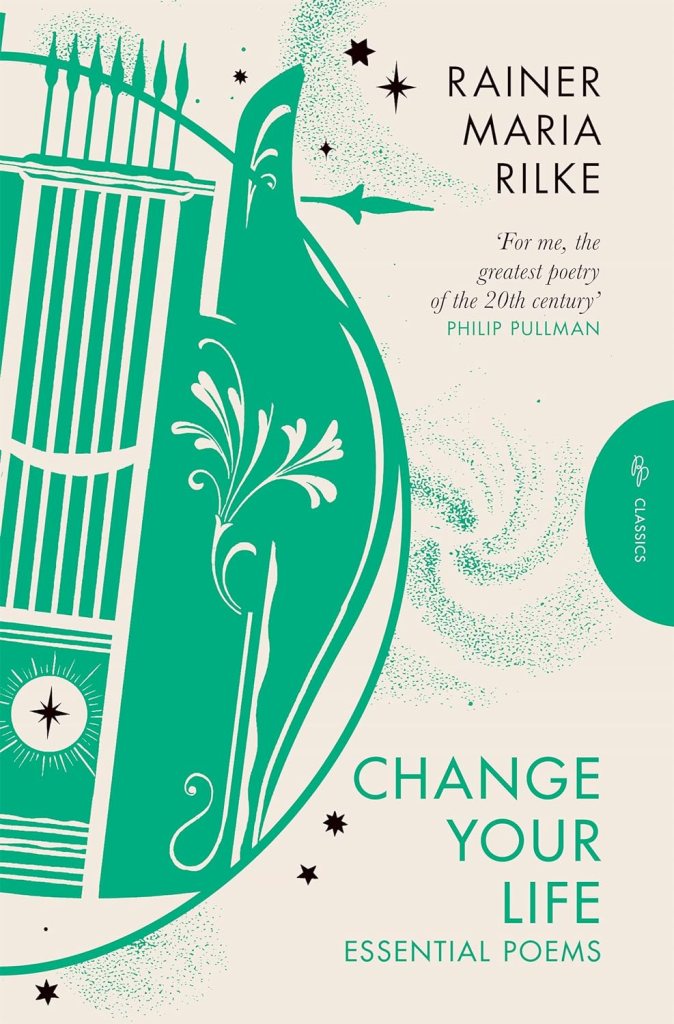

The idea of lives of the dead altering the lives of those they have touched in life is familiar enough, though I was working on my translations of Rainer Maria Rilke around this time and I’m sure his influence is in here. It is not just the remembering of a friend who has passed away, but also that our own perceptions of ‘a house, a street, a flowering tree’, for want of a better word, spiritualises the material object, giving it a life, a light, an existence, beyond the ordinary. The resurrection of the bugs stomped by my daughter in what follows is probably an allusion to the early primitive computer games the kids used to play in which a failed – hence fatal – leap from a high building would result only in a brief ‘death’ and their 1st person avatar would soon revive and carry on in pursuit of adventure.

x

In Hornsey Central at 570

this morning, I found books to undermine

my daughter’s smiling confidence

that bugs she crushes beneath her shoe

lie dead a while, then revive good as new.

x

At 790, I leafed through life and death

in Ancient Egypt for her older brother:

how they wash their dead in water and oil,

then bind them in linen smeared with gum

and priests wrap lucky charms inside

x

in hope that none will break the seal

till the dead themselves in time of need.

x

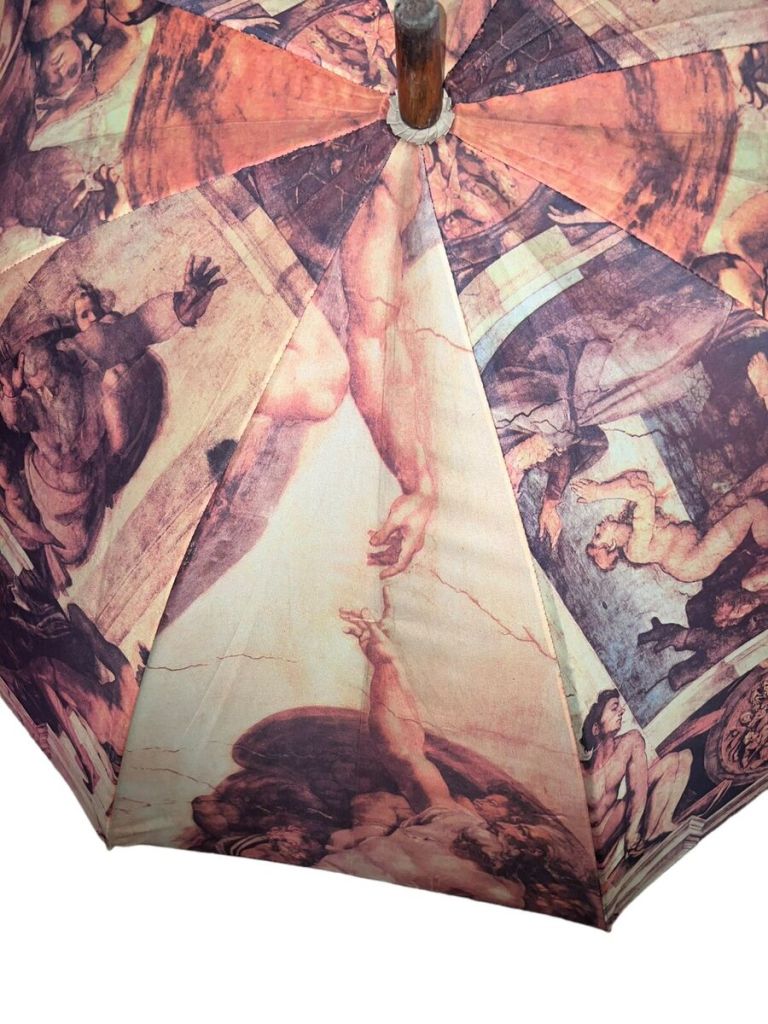

The ‘lucky charms’ idea naturally led the poem on to what I myself might place in a good friend’s sarcophagus and gave rise to a list of his multifarious likes and loves, concluding with the heartfelt wish that his (prematurely unhirsute) head might – even in death (though he had no religious belief as far as I know) – remain somehow protected. The image on the underside of Laurence’s umbrella is a truth!

x

Then I’ll wrap Homer for you, Wolves black-

and-gold, your Micra, Marvel, Blockley

and booze, moist, sweet cake for the road,

x

Frederick Leighton, Sir Frankie Howerd,

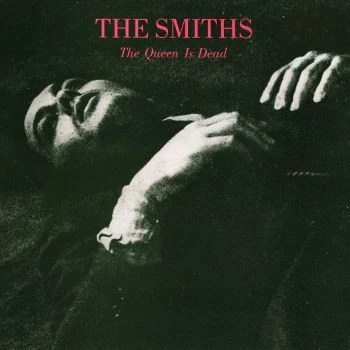

Wisden, The Smiths and that Italian umbrella

you flourished one day and thundered open –

behold! the Sistine roof appeared

to keep your bald head from the hissing rain.

x

‘The umbrella and the bay tree’ was originally published in An English Nazareth (Enitharmon Press, 2004).