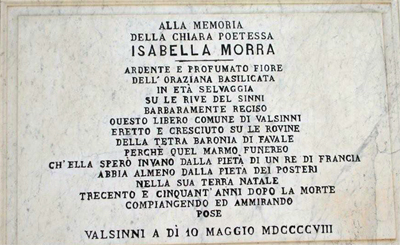

While travelling in the Basilicata region of Southern Italy – in effect, the arch of the ‘foot’ of that country – researching her earlier translations of the little known twentieth century male poet, Rocco Scotellaro (1923-1953), Caroline Maldonado heard of the much earlier, even less known poetry of Isabella Morra. Born around 1520, Morra was one of eight children. Her father, Giovan Michele fled into exile in France when Isabella was about eight years old. A cultured woman – knowledgeable in science, music, literature and the classics – her life prospects were utterly curtailed by her father’s absence and she was left in the care of her brothers.

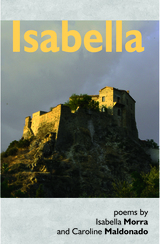

Her resulting frustrations may be imagined – and astonishingly they are also vividly portrayed in her poems – but her violent death, aged 26, is not clearly understood. There were rumours of an affair between Isabella and a Spanish count and poet, Don Diego Sandoval de Castro, though he was also the husband of a friend of Isabella’s and almost certainly admired by her as much as a writer as a man. But her brothers believed the rumours and seem to have killed her – an honour killing to protect the family name. Maldonado’s book, Isabella, published by Smokestack Books, contains – in parallel text – all of Isabella’s known work, just ten sonnets and three canzoni. The book also includes Maldonado’s own introduction to Morra and 17 original poems by her, inspired by Morra’s work and her “strange, pitiful tale”.

Given the period in which she wrote, it is the raw, personal nature of many of Morra’s poems, their direct style of address, that is so surprising. Maldonado’s decision to make the work as “accessible as possible to a contemporary reader” accentuates this as does her choice not to re-create closely the rhyming of the originals. Morra creates a strong sense of an actual place. It is a place of imprisonment, one she loathes, the village of Favale: “this vile, odious hamlet”. She looks favourably on neither the place nor its people:

Here once again, O hell-like wasted valley,

O Alpine river, shattered heaps of stone,

spirits stripped bare of all goodness or pity,

you will hear the voice of my endless pain.

An unsympathetic ear might sense something brattishly self-regarding here and, given her youth and sheltered upbringing, that would not be surprising. But it is partly this sense of a little girl lost that is so moving. There are several sonnets concerned with her father’s absence. Sonnet III addresses him directly:

I, your daughter Isabella, often look out

hoping for a wooden ship to appear,

Father, that will bring me back news of you.

The first line’s poignant allusion to their relationship reminds the reader that he has been absent from her life for many years. As she gazes out hopefully, she and the dismal locale seem to merge, “so abandoned, so alone!” In sonnet VIII, ominously anticipating the end of her life, she imagines her father’s too-late return: “Tell him how, by my death, I appease / my bitter fortune and the misery of my fate”. It is the capricious – even vengeful – Goddess ‘Fortuna’ that Morra often rails against. In Sonnet I, she is assaulted by “cruel Fortune”. Sonnet VI is a tirade against her mistreatment, initially from a literary standpoint (Morra had hoped to make a name for herself “with the sweet Muses”):

You have promoted every minor talent,

Fortuna, rewarded every sordid heart,

you now compel my own, long past all tears,

to face still more hardship, feel more desolate.

Fortune is also berated for bringing down King Francis I (defeated in battle in 1544), the French monarch who she hoped might protect her father and even bring about a reconciliation between them. Fortuna’s femininity leads Isabella into the awkward position of maligning all women in saying that Fortuna is an “enemy to every noble heart”.

Given such a small body of work and uncertainties about its editing and arrangement, it’s hard to be certain of any sense of development. But over the ten sonnets Maldonado gives us, Morra’s complaints about her lot do seem to modulate into something more resigned and accepting. This is more the tone of Sonnet IX, in which “unholy Death or cruel Fortune” are again the enemies of her “rising hopes” but there are signs of greater resilience: “worn down as I am it will do me no harm”. The final Sonnet also takes up a more distanced perspective:

You know, in those days, how bitterly I wrote,

with what anger and pain I denounced Fortune.

No woman under the moon ever complained

with greater passion than me about her fate.

What has given Morra greater strength is her religious faith: “Neither time nor death, nor some violent, / rapacious hand will snatch away the eternal, / beautiful treasure before the King of Heaven.

A similar progression shows itself in the three canzoni too. A modern reader is likely to find her early passionate rebelliousness most engaging, the lines in which she says she will use her “rough, unpolished tongue” to rail against her dismal fate. It’s Fortuna again who is identified as the culprit, plaguing her “ever since the days of milk and the cradle”. One of her complaints is that she has never had the opportunity to hear her own beauty praised and the loneliness and frustration of this young woman is perhaps transformed into the passionate address of the second canzoni. It takes its place in that tradition of religious poems which express a spiritual fervour through language that can be hard to distinguish from the words of a more fleshly lover. Morra appeals to Christ: “I will love only you”. She will use her skill in words to “sculpt [his] heavenly body” and she proceeds to describe his forehead, eyes, hair, neck, lips, hands and feet. The canzoni’s traditional five-line envoi on this occasion is a sort of breathless admission of the impossibility of her task, though even here, the passionate feelings are unmistakable:

Canzone, how crazy you are,

to think that you could enter the sea

of God’s beauty with such burning desire!

The third canzoni – as did the final Sonnet – takes up a longer perspective in which the landscape of her actual imprisonment has become a more symbolic location: “To be in these dark / and lonely woods in days gone by / used to burden my heavy body”. It’s impossible not to think of Dante’s much earlier journey through the “dark wood” of despair. Morra also suggests she has emerged from its dangers, walking now “along solitary roads / far from human intrigue”. We sense a new humility; whether metaphorically or not, she presents herself as “dressing my frail body in rough clothes”. How distant in time we’ll never know, but Morra has evidently travelled a long way from those earlier complaints at her unjust treatment. Especially in the third canzoni, her delight in the natural world rings genuinely true and through that natural world she sees God – or rather “God’s great Mother”, Mary, the female figure who has now ousted the hated Fortuna.

Morra’s own few works end on such a note of resolve and hard-won redemption. That she faced a brutal and unjust murder at the hand of her own family is brought out more clearly by Maldonado’s own poems. She is partly interested in the contrast between the more contemporary (and male) poet, Scotellaro and the fate of Morra. As she has surely done in producing this fascinating little book, Maldonado intends to give Morra a voice in many of these new poems and, in ‘Scirocco’, we hear this imprisoned young woman poignantly repeating, “Who will ever hear me?” Both translator and publisher are to be congratulated in this recovering of an almost lost female voice from Renaissance Italy.

Hi Martin

Did you receive my earlier email asking whether you might be willing to write a testimonial for my first full collection?

Best wishes

David Gilbert

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLike

Hi David I did and suggested you email me? mcrucefix@sky.com

LikeLike

[…] While happy to accept the desire of the poet to maintain a distance between the lyric/dramatic ‘I’ and her autobiographical self, I find the idea, the ‘as if’, of this composite authorship hard to take. There is even something disproportionate about the claim of identity between the two women, given the extremity of Juana’s life-long suffering. I’m reminded of Caroline Maldonado’s 2019 book, Isabella (Smokestack Books) in which she translates and writes poems to Isabella Morra, an Italian aristocrat of the 16th century who also suffered appalling hardship (and likely murder) at the hands of her male relations. But Maldonado’s interest in the historical figure is never claimed as an identity. (I reviewed this book here). […]

LikeLike