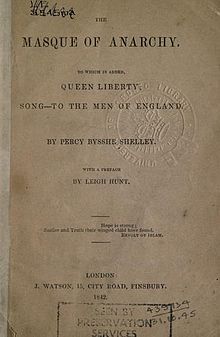

Having recently seen Mike Leigh’s powerful rendering of the events leading up to and including the so-called Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819, I re-read the poem Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote as a direct and angry response to those events, a poem Richard Holmes and Paul Foot have called “the greatest poem of political protest ever written in English”. In my twenties, I spent several years writing a PhD thesis on Shelley’s work – more on his ideas about language than a conventional lit. crit. of the poems – so it’s a curious pleasure coming back to this poem after all these years. And perhaps it does not seem in need of much explanation, written as it was so self-consciously to reach as wide an audience as possible to achieve its political impact. Yet its driving ballad-like form hardly gives the reader time to reflect and there are areas of obscurity within it – apparently real uncertainty on Shelley’s part. Of course, the political climate at the time (as Leigh’s film so vividly demonstrates) was increasingly repressive in regard to any speech or publication in favour of Reform. Even the radical Leigh Hunt – to whom Shelley sent the poem from his exile in Italy – refused to risk publication. The poem eventually saw the light of day only after the Reform Bill had been passed in 1832.

A Voice from Exile (ll. 1-4)

The whole poem is notable for the multiple distances Shelley maintains from the actual events of August 1819 (there is no poetic reportage of any kind, though he had read several newspaper accounts), in his own remote position (he had fled England in 1818, never to return) and in the way in which the poem comments on political realities (through the filters of ballad form and caricature and the sophisticated layering of voices). The opening quatrain briskly deals with the geographical distance, though with something of the air of a fairy tale.

As I lay asleep in Italy

There came a voice from over the Sea,

And with great power it forth led me

To walk in the visions of Poesy.

The AAAA rhymes here announce the poem with a series of thumps like an overture to wake his listeners and perhaps also himself from his guilt-ridden sleep, so far distant from the causes of political reform and revolution that he had long supported in England. The “visions” of poetry immediately give license to the strange encounters that follow.

The Triumphal Parade of Anarchy (ll. 5-37)

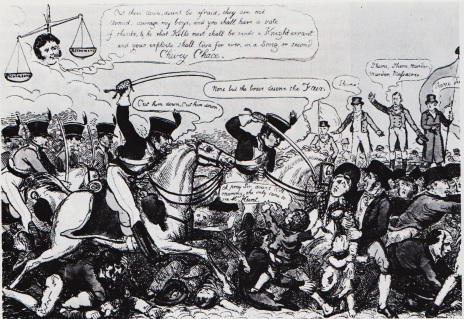

The kind of gothic caricature that dominates the following stanzas has often been linked to the style of political cartoons by Hogarth and Gillray. But Shelley’s adolescent love of the gothic genre is well known and the resulting mix is all his own. The reader (accompanying the narrator’s “walk”) is thrown into a parade of characters who precede the climactic appearance of the personification of Anarchy himself.

This is the “triumph of Anarchy” (l. 57) in the sense used by the Romans as a victorious parade through city streets. The narrator meets three main figures – Murder, Fraud and Hypocrisy. Reversing the usual method of personification, each abstract figure wears a mask in the guise of a contemporary politician – the Foreign Secretary, Castlereagh, the Lord Chancellor, Eldon and the Home Secretary, Sidmouth. The satirical effect of these masks is driven home by the figures’ actions. Castlereagh feeds human hearts to the dogs that follow him, Eldon sheds tears that turn into mill-stones and children have “their brains knocked out by them” and Sidmouth, clothed equivocally by both Bible and “night”, rides by on a crocodile (more false tears, geddit?).

Shelley glancingly refers to “many more Destructions” traipsing along in this “masquerade”, and they are all “disguised, even to the eyes, / Like Bishops, lawyers, peers, or spies”. The enemies of the people are therefore boldly named and it’s clear that the poem’s title contains a pun on mask/masque, alluding to the paper-thin disguises that the abstractions of corruption and injustice wear as well as the arrogant self-regarding performance of the triumph or parade they are taking part in. The climax of this parade is the approaching, apocalyptic figure of Anarchy himself:

Last came Anarchy: he rode

On a white horse, splashed with blood;

He was pale even to the lips,

Like Death in the Apocalypse.

And he wore a kingly crown;

And in his grasp a sceptre shone;

On his brow this mark I saw–

‘I AM GOD, AND KING, AND LAW!’

Anarchy here means a state of lawlessness in which the rich and powerful are freely able to control all religious, state and legal power. Their laws preserve their own freedom to exploit. We’ll see a bit later that Shelley had a concept of the “old laws of England” (l. 335) that he believed had been overridden but that once had served to protect the lives of ordinary people.

England Under Anarchy’s Rule (ll. 38-85)

Shelley’s poem broadcasts and accelerates the trope of the parade (“With a pace stately and fast”) to show the appalling results of this rule of the rich and powerful across the whole country. There are echoes here of the charges into the crowd at St Peter’s Field in Manchester:

And a mighty troop around,

With their trampling shook the ground,

Waving each a bloody sword,

For the service of their Lord.

Their Lord here is Anarchy himself whose pageant is now seen to be passing through England, “Drunk as with intoxication / Of the wine of desolation”. It lays waste to everything, tearing up and trampling down, eventually arriving in London. Ordinary citizens feel terror and panic while the supporters of Anarchy flock to him, repeating the slogan and self-announcement written across his brow. Those who flock to his side are lawyers and priests and:

The hired murderers, who did sing

`Thou art God, and Law, and King.

We have waited, weak and lone

For thy coming, Mighty One!

Our purses are empty, our swords are cold,

Give us glory, and blood, and gold.’

Anarchy bows in response to this obeisance with a false and aristocratic grace (“as if his education / Had cost ten millions to the nation”) and recognises the bases of his power are secure in Palaces and quickly to be seized in the Bank (of England) and the Tower (of London), after which he anticipates meeting with a compliant, “pensioned Parliament” to further confirm the rule of Anarchy in the England of 1819.

Hope and the Mysterious Shape (ll. 86-125)

But as Shelley’s sentence crosses the next stanza break – ie. without any clear pause – the seemingly unstoppable parade of bloodshed, inequality, injustice and hypocrisy is strangely interrupted by a counter personification. A crazed-looking young woman (“a maniac maid”) runs out declaring that her name is Hope, though the narrator says “she looked more like Despair”. The perception here is interesting as even Shelley’s narrator has been so infected by the toxic atmosphere spread by Anarchy that the girl (who is soon to bring about a challenge to Anarchy) looks to be insane and more resembles the absence of hope than otherwise. This is one of Shelley’s core political beliefs and had already appeared in the closing lines of Prometheus Unbound. There, Demogorgon urges optimism in the long term conflict with abusive power: “to hope, till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”. The movement for Reform will – it seems – have to come close to despair, or its own wreck, before the powers of Anarchy are likely to be defeated.

But as Shelley’s sentence crosses the next stanza break – ie. without any clear pause – the seemingly unstoppable parade of bloodshed, inequality, injustice and hypocrisy is strangely interrupted by a counter personification. A crazed-looking young woman (“a maniac maid”) runs out declaring that her name is Hope, though the narrator says “she looked more like Despair”. The perception here is interesting as even Shelley’s narrator has been so infected by the toxic atmosphere spread by Anarchy that the girl (who is soon to bring about a challenge to Anarchy) looks to be insane and more resembles the absence of hope than otherwise. This is one of Shelley’s core political beliefs and had already appeared in the closing lines of Prometheus Unbound. There, Demogorgon urges optimism in the long term conflict with abusive power: “to hope, till Hope creates / From its own wreck the thing it contemplates”. The movement for Reform will – it seems – have to come close to despair, or its own wreck, before the powers of Anarchy are likely to be defeated.

Hope’s father is Time, whose other children – these are the previous occasions when the cause of liberty and reform had been strong – are covered in the “dust of death”. So Time has brought forth a new opportunity though the actions of the young woman called Hope are surprising. Less Joan-like, more Christ-like she simply lies down before the trampling hooves of the triumph of Anarchy. But moments before she too is about to be trampled into dust:

[ . . . ] between her and her foes

A mist, a light, an image rose,

Small at first, and weak, and frail

Like the vapour of a vale

This mist – later called a “Shape” – is one of the mysteries of the poem’s politics. Hope provokes its appearance. At first weak, it gathers in strength. Shelley compares it to clouds that gather “Like tower-crowned giants striding fast, / And glare with lightnings as they fly, /And speak in thunder to the sky”. In the next few stanzas it becomes more soldierly, “arrayed in mail”, compared to the scales of a snake (for Shelley the snake was usually an image of just rebellion not of evil), yet it is also winged. It wears a helmet with the image of the planet Venus on it. It moves softly and swiftly – a sensed but almost unseen presence. And rather than any military action or campaign of civil disobedience, this Shape, conjured by Hope, creates thinking:

This mist – later called a “Shape” – is one of the mysteries of the poem’s politics. Hope provokes its appearance. At first weak, it gathers in strength. Shelley compares it to clouds that gather “Like tower-crowned giants striding fast, / And glare with lightnings as they fly, /And speak in thunder to the sky”. In the next few stanzas it becomes more soldierly, “arrayed in mail”, compared to the scales of a snake (for Shelley the snake was usually an image of just rebellion not of evil), yet it is also winged. It wears a helmet with the image of the planet Venus on it. It moves softly and swiftly – a sensed but almost unseen presence. And rather than any military action or campaign of civil disobedience, this Shape, conjured by Hope, creates thinking:

As flowers beneath May’s footstep waken,

As stars from Night’s loose hair are shaken,

As waves arise when loud winds call,

Thoughts sprung where’er that step did fall.

The Shape has variously been interpreted as liberty, England, the people, revolution, nature, intellectual illumination. But I think the image of Venus suggests that the Shape is Love which, in Shelley’s ‘A Defence of Poetry’, is synonymous with the Imagination, the expression of which is Poetry. Poetry here is a cultural and perceptual shift (artists and writers are merely one aspect of its manifestation). At its heart, is the rejection of reason which perceives and depends on differences and the embrace of a mode of perception that favours similitude, including the similitude between all people and classes.

The Death of Anarchy (ll. 126-146)

How exactly Love, so broadly defined, brings about the dramatic consequences detailed in the next few stanzas is unclear. There seems to be evidence of a battle as Hope is suddenly seen walking calmly, though “ankle-deep in blood”, and Anarchy himself is reduced to “dead earth upon the earth”. In the light of the bloodshed at Peterloo, such actual conflict and resulting casualties are hardly surprising but the use of force by those seeking political reform seems to contradict Shelley’s later pronouncements in this poem. The only alternative is that the blood she wades through is that spilt by the powers associated with Anarchy.

Yet in the calm aftermath of these events, there comes a sense of renovation, a “sense awakening and yet tender / Was heard and felt” and, most importantly, there are further words. This time the speaker is unclear though it is “As if” the earth itself, the mother of English men and women, feeling such bloodshed on her brow, translates this spilt blood into a powerful, irresistible language, “an accent unwithstood”. Shelley repeats “As if” once more, confirming the mystery of this voice, a voice which proceeds now to speak the whole of the remainder of the poem. For Shelley, Poetry in his broad sense is “vitally metaphorical” and the earth’s imagined speeches convey a sense that the cause of liberty is in accordance with the truly understood (surely Rousseauistic) nature of creation.

Yet in the calm aftermath of these events, there comes a sense of renovation, a “sense awakening and yet tender / Was heard and felt” and, most importantly, there are further words. This time the speaker is unclear though it is “As if” the earth itself, the mother of English men and women, feeling such bloodshed on her brow, translates this spilt blood into a powerful, irresistible language, “an accent unwithstood”. Shelley repeats “As if” once more, confirming the mystery of this voice, a voice which proceeds now to speak the whole of the remainder of the poem. For Shelley, Poetry in his broad sense is “vitally metaphorical” and the earth’s imagined speeches convey a sense that the cause of liberty is in accordance with the truly understood (surely Rousseauistic) nature of creation.

Thank you for highlighting what I think, is Shelley’s magnum opus. I do not think he has written anything finer. Yes, Hunt had to wait to publish, he was actually threatened by a man in an alley who somehow got a hold of the poem, hence his trepidation. I would add that the personification of certain elements such as Hope and Death, (what was termed and a conversation poem and really originated with Coleridge) serves to bring the reader out of the narrative while underscoring the elements that drove the conditions at that time. Castlereagh with his troops coming into squelch any uprising by the masses who were of all things (as is noted by many) asking for LOVE by their signs, and the equal treatment of workers. One must if they look at today’s inequities, acknowledge the continuing parallels. Shelley, would if he were able to rise from the dead, surely mourn the lack of progress we have made.

LikeLike

[…] hope you have read my earlier post on this subject because here comes my commentary on the second half of Shelley’s The Mask of Anarchy. […]

LikeLike