This week, I sat down to write a thinking piece about C S Lewis’ brief memoir about his wife’s death, A Grief Observed (published under the pseudonym N W Clerk by Faber in 1961), when this happened instead.

My father died – I’m shocked at the passage of time – just over 8 weeks ago. At the age of 97, it was hardly unexpected though to be honest I had anticipated my mother (age 95 this month and seemingly physically far more frail) to be the first to leave the world. Though hardly unexpected it was still a surprise. It happened late at night – I’d travelled back to London thinking he was stable enough. By the time I’d returned the next day to the Care Home in Wiltshire, the undertaker had already taken him away. There were so many distractions, things to sort out, though we’d already sold the family home and his affairs were as simple as can be for a man with two savings accounts, a couple of State benefits and an utterly derisory works pension.

I did decide to visit him in the undertakers’ so-called chapel of rest. I’m not sure this was about saying goodbye – though circumstances had meant I hadn’t done this in any conscious way. The assistant took me into a little hallway where a door stood open, some classical music playing. A wooden chair and a table with a vase of flowers were all to be seen in the hallway. I have no recall of the music or the type of flowers. I was taken aback when she explained that some people prefer simply to sit outside the ‘chapel’ rather than go in to view the body. I felt reassured somehow that such a reluctance was not something I was feeling and it would be a sort of cowardice if I did. I felt brave, or just a bit braver. I was doing this for Dad. Though her observation then made me re-consider. Maybe I was really anxious, even fearful, about seeing him. I sat in the chair outside for a few minutes to see how it felt.

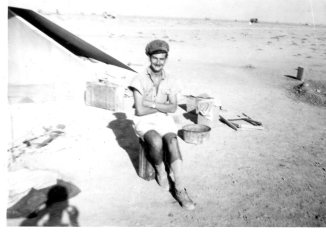

It felt pointless. I was here to see him and to have done with it. I edged round the open door. The coffin was deliberately around the corner, out of sight until you got well into the room. It filled an alcove, supported at waist height, I supposed, on some sort of trestle. I’m enough my Dad’s son to think of such things. Later on, after I’d sat a while in the chapel I started looking – as he would have done – at the structure of it. It was just a plain room, almost certainly separated off from an original larger room. There was an RSJ across the width of it. Perhaps there was another such ‘chapel’ next door. Semi-detached. Like the house Dad had lived in. In fact, the one he’d help build in the mid-1950s. I was taken there at the age of one. I left there to go to university at the age of 18. We’d sold it for more than we’d expected about a month earlier. Semi-detached.

They’d put a crucifix on the wall above the coffin. Or rather, the cross was a fixture on the wall. Other coffins in series had lain beneath it. Dad always had a dislike of religion. I never could get to the bottom of why. Born in 1920 you’d have thought it would have been just part of the landscape he grew up in. Was it rammed down his throat to the point of the need to vomit it back up again? Was there something in his war years that made him see through it so vigorously that – even into his 90s – he never found a way back? His wife was quietly non-conformist, mostly Methodist. I’m sure she would have attended church in these more recent years (her younger sister regularly did). I’m sure she stayed away because of his hatred of it. Now here he lay under a crucifix in an inappropriately ‘holy’ setting with such tasteful lighting. Hurrumph, he might have said. Words were not his thing. I never showed him this little poem:

Words and things

Past ninety and still no books to read

your knuckles rap the laid table

gestures beside a stumble of words

so much aware of their inadequacy

it hurts us both in different ways

since a man without language is no man

finding too late this absence of words

builds a prison you’re no longer able

to dominate objects as once you did

the world turns in your loosening grip

I still feel a bit guilty about having written it. Agenda published it originally. It’s just appeared in my new book. But no – he never saw it. I made sure of that.

I looked at him in his box. My brother and I had decided not to dress him in his own clothes. His only suit was so old and shabby and he had little else that we thought was suitable (why did we agonise over it – I was the only person who knew him to see him in this state anyway). Oh for his old suit! He was dressed in a sky blue silk number, a ludicrous ruff about the neck: a sort of choir boy outfit. My main impression was of the newness of the cloth of the robe, its strong vibrant colour against the chilly greyness of what must lie underneath if his hands were anything to go by.

Then at last, I looked directly into his face. I’d been reading Lampedusa’s The Leopard and at the end of the novel, the dying Prince, Don Fabrizio, looks at himself in the mirror and wonders why “God did not want anyone to die with their own face on?” The last time I’d seen Dad was after he’d been brought out of hospital, back to the Care Home where he lay sleeping for hours on a mattress on the floor (to stop him rolling off and injuring himself). He puffed and blew a good deal, eyes shut. He rummaged his legs to and fro, tying the bed sheet in knots. But he never woke. In those hours, it seemed to be him. I sat beside him with my mother. I held his cold hand and repeatedly told him we were there, we were there for him, he was OK, he was not in hospital (god how he hated hospitals!).

But the face looking up out of the coffin seemed to be somebody else. Hard to tell what was plain natural death, what was the undertaker’s art, what the lighting, what my weird state of mind. All the clichés about the waxy, smooth look of the dead are true. His Crucefix nose – always fairly prominent – launched from his sunken cheeks and bony brow skywards. His chin – which in life was always weak and receding – also thrust forward and up in the most unnatural way. What had they done? What had they packed his jaw with to achieve this cartoon effect? His mouth with its pencil thin lips (plenty of times I thought them mean lips) was shut very tightly. I wondered if it was sewn shut? I wondered if they had left his dentures in? His eyelids – which in those last few hours of puffing and blowing, had often been leaking open, a segment of watery eye visible though no inner sight seemed ever to have registered – his eyelids now were also tightly bound. Closed down. Closed down long before the undertaker’s craft took hold. Now physically closed down to reflect the inner closing down that had taken place in my absence.

As I stood beside the coffin and looked down, I had the powerful sense that he was not there. Not merely that this did not resemble the man I knew but more than that – he, in himself, was not there. He had departed the physical form that lay there more or less recognisable. I don’t think he was elsewhere. I’ve been with him on that bit of religion for decades now. But I still felt some relief. On his behalf perhaps. Recently he had been more muddled and fearful, obsessive about some things, angry about others. Life seemed to have very few pleasures left; lots of panicky moments, angry self-hatred, suspicions of people, distrust, downright fright. He was no longer living in that horrid morass. That must be some relief.

He was not there. But the hands, propped also choir boy style on his chest, clutching incongruously a white rose, were definitely still his. Emerging out of the stupid silky blue sleeves, the long bony hands were still familiar. How they used to float vaguely, not elegantly, but sometimes delicately, trying to add whatever was always lacking from his words, wafting to and fro following the right and left turns to the municipal dump, to the only local shop not closed down, to the bus stop (their life-line into town).

I never once touched him. I thought of the coldness. The lack of give, of elasticity. I didn’t think he’d mind. We seldom touched in life. But I did talk to him. I said I was there. I said goodbye. Those two things over and over again. My eyes and throat filled as I tried to say them aloud.

In the end there was no more to do. He was not there. I was in a room with a box and some kitschy lighting. I sidled back out round the door. I looked back in, feeling, of all things coquettish, as if I might surprise him about to move, to sit up and grin, it was all a joke. No. He was not there. He was not coming back. Not this way.

I went out through the hallway, past the flowers again, the music receding, out into the front room of the undertaker’s shop. The assistant was not around. I gathered my bags and left. The daylight was white. Two men were slumped nearby drinking from tin cans. They looked up at me. I suppose they had seen the door I’d come out of. Perhaps I had death all over me. The High Street seemed tissue-thin, like a poor stage-set. Everybody else actors. I walked down it, then back up, unsure where to go. In the end, I sat in a pub for an hour over two pints of bitter. My train was not till around 6pm. I passed the time googling an old girl-friend’s name.

Martyn you’ve inherited that profoundest gift, your father’s understanding of war, disaster: survival after death in the words of a poet, continuity through family, those unfading flowers, immortelle.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very beautifully written

LikeLiked by 1 person

My condolences to you, Martyn. My mother died unexpectedly at ninety-one, a couple of months before I came to your Brueghel workshop in Bath. Whilst ninety-odd may sound old to those who didn’t know her, as the one who did that number did not reflect her back to me – a sense I get too from what you’ve written about your father. Eight weeks is longer than the summer holidays to a child, but nothing against the yardstick of grief. Wishing you strength for however long and whatever way to move through, with, your loss.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Leanda. Lovely to hear from you and thanks for those thoughts. Hope your writing is going well.

LikeLike

Thank you, Martyn. Yes, I’m writing a few things, including sporadically some prose around my mother’s life. I came across a poem on my computer last week when looking for something else, that eventually I realised I’d written myself! Could do with a few more of those at present, but editing is always my best thing for times when nothing new will come. Thanks again for the workshop: I really enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Regardless how old one is, when a parent dies one becomes an orphan.

Condolences for your loss.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just got round to reading this, Martyn. So beautifully expressed and very moving. It was a privilege to read. My thoughts – to you.

LikeLike

Martyn –

Your “Grief Observed” is a moving piece. Like others here, I am honored to have read it. Grief, while unique to each of us, has a common thread that stretches across even more than three-thousand miles. I am sorry for your loss.

Denise

LikeLike

Hi Denise – gosh that’s rather marvellous to hear from you after all this time. Thanks you for your comment and your time reading. I hope you are well – and your family – hard to resist the sense that we are at the other end of life now rather. I wish you health and happiness.

LikeLike

Martyn,

I stumbled across this while Looking for info on the 60th anniversary of Marshmead Self-Build celebrations, a project both yours and my Father were involved in. I’m planning to get him there for a walk down memory lane for us both. You seem to be able to put into words things that rattle around in my mind but I could never express.

I feel proud to have known you.

Bruce (One of the annoying kids next door)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Bruce – how amazing to hear from you – do send my best wishes to the whole family. Are your mum and dad still both with us? dad died a couple of years ago now – as you’ll realise – and Mum is in a care home in Chippenham. Are/were there celebrations for the 60th? I’ve thought a lot about the whole self-build project in Marshmead – how important it was to our growing up – though we knew little of it at the time. Our mucking about – going fishing- with you and Kim especially was a wonderful time. I trust you are well – still living on the south coast? – and I suppose we are all getting close to retirement ages now – madness. As it turned out, I spend a lot of my time trying to put words to feelings and am chuffed beyond words if you think some of it works. I was a bit nervous about posting this one on Dad’s death but the number of very positive responses has justified the risk I think. Wishing you all the very best.

LikeLike

[…] house itself? A little tugging of nostalgia here (we eventually sold the house after my parents’ deaths just a few years ago) but mostly I sense information welling up. An estate of 40 such houses on the edge of a Wiltshire […]

LikeLike