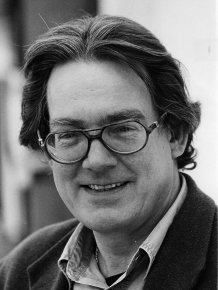

I met poet, translator and critic, Hilary Davies, back in the early 1980s and our paths have kept crossing since. She was one of the first intake of women undergraduates at Wadham College, Oxford, where she read French and German. She won an Eric Gregory award in 1983, has been a Hawthornden Fellow and chair of the Poetry Society (1992–3). With David Constantine, she co-founded and edited the poetry magazine Argo and has three previous collections of poetry (published by Enitharmon): The Shanghai Owner of the Bonsai Shop (1991); In a Valley of This Restless Mind (1997); Imperium (2005). She was head of languages at St Paul’s Girls’ School, London, for 19 years and was married to the poet, Sebastian Barker, who died in 2014.

Davies’ new collection, Exile and the Kingdom (Enitharmon, 2016), is framed by two very powerful sequences. It opens with ‘Across Country’, a series of seven poems which add up to an autobiographical ‘growth of the poet’s mind’. The book concludes with ‘Exile and the Kingdom’ itself, a further eight poems which are nothing less than a meditation on the poet’s raw grief and re-discovery, or reassertion, of her religious faith. Both sequences contain weddings.

‘Across Country’ opens with an evocation of a child’s first moments, “what gets forgotten”, in a state of inarticulacy, no ability to exert our own will, with no will even, language-less and effectively silent, being “carried by gods”. Passive in the hands of mother and father, the journey variously begins in “The reindeer saddle and the motor car, / the sighing desert and the plateau wind”. Davies seems to suggest these first human experiences fall onto a tabula rasa as they “Etch the first surfaces of particularity / And settle in our souls”. The particular development traced here is Davies’ own, of course, and crucially this involves a later period of travel in France. Happily alluding to Wordsworth’s own tracing of his youthful days and Revolutionary enthusiasm in France (“Bliss it was in that dawn to be alive /But to be young was very heaven” – The Prelude, Book 11), Davies praises “the glory of the cornfield and belltower, / Granite, limestone, vineyard and cloister”. As with Wordsworth, France offers an experience of human love, but Davies is also drawn to intellectual pursuits, the thrilling confusion of “many minds passing”, arguments of “polity and governance” and to the “meretricious fruit / Of the ideology tree”. We are being told this in order for such concerns to be ultimately dismissed:

The lords of existence

Are neither economist nor philosopher

The Lord of existence

Shows himself not in systems

The fourth poem in ‘Across Country’ seems to record the young woman’s first realisation that religion was to be the answer to many of the questions she was asking: “I crossed into church after church that summer, / Thinking of erudition, but beside me trod Love”. The capitalisation and conventional personification makes it clear that Davies is deliberate and happy to place herself in a long tradition of poetry dealing with religious experience; there is no radical re-making of poetic form or language. Davies does not use masks. Discursive passages are in unrhymed, fairly irregular paragraphs which are punctuated every so often with more lyrical rhyming passages, song-like.

Poem five of ‘Across Country’ is just such a lyrical piece, portraying a wedding, but not one that lasts:

Hate has eaten my bridegroom’s heart

And remorse is become my fury

Now I must go the road of affliction

Searching for mercy.

That search, Davies argues, is more a matter of “Waiting, not willing”. It is the traditional negative road in the sense of the centrality of “self-surrender”, imaged in the seventh poem as the sensation of being on a boat on a threatening ocean: “No measure but the dark blue breathing of the opening deep, / Where personhood dissolves beyond mere terror”. I don’t share Davies’ faith but I share her belief that, in terms of our daily acts and choices, we are to be judged in the long run: “Only perdurance delivers”. And in terms of the nature of those acts and choices, whatever set-backs are faced, we need to be accompanied by that same figure who walked beside her into the churches in France: “what love is, and does”. Read as the record of the poet’s experiences, it’s likely that this opening sequence concludes with Davies meeting with Sebastian Barker, the beginning of new happiness (“I knew instantly I had to go the hard way with you / To learn how to love better”).

.

The central sections of this collection are made up of poems more directly engaged with the contemporary world of north London, Stamford Hill, Walthamstow, the valley of the River Lee, Abney Park in Stoke Newington (I blogged one of these poem’s a few weeks ago). There are also poems more explicitly concerned with the relationship with Barker with titles like ‘Night’s Cloak’, ‘Aubade’, ‘Love Song’. I’ve always thought it a premature admission of defeat to declare ‘happiness writes white’ but some of these poems slip too easily into a mode in which this reader feels more like eavesdropping than sharing the experience of years of happy marriage; technically there is a flowering of lyricism and some softening of the vocabulary. On the other hand nobody is going to read these poems and not be thinking of Hardy’s tributes to Emma Gifford – it seems whether the marriage was mutually loving or not, the sense of loss remains overwhelming.

This is where the concluding sequence picks up though there is no need to narrow Davies’ focus wholly to the autobiographical. As I’ve said, these poems are in the tradition of religious verse and there are passages here that stand comparison with the Eliot of the Four Quartets. The opening poem – a little sequence in itself – paints a state of despair, initially social and political, latterly more personal:

Then there’s the heartache

At the core of things: attachment, the blank certainty

Of letting go, the arbitrary wing of accident,

Wrong gene or partner, a lifetime bled into the dusty ground

Of non-fulfilment, the waste [. . . ]”

The temptation is to try to counter this by accepting “ourselves as measure”, to focus simply on career, material gain, simply being busy, keeping warm. That this is never enough in itself is suggested when Davies recalls a favourite uncle who, having apparently a comfortable and successful life kills himself. For the young Davies what this taught was clear: “the impossibility of loving begets despair, / And despair kills”. The third poem of ‘Exile and the Kingdom’ seems to mark the beginning of the end of exile and returns to one of the many French churches mentioned in the earlier sequence.

Out of the bustling Parisian streets, the narrator turns aside and understands, “Even if I have all gifts without love I am nothing”. As in Four Quartets, Davies mixes philosophical discursiveness with personal reminiscence and poem four recalls a Christmas morning in a country church. The priest, apparently ill, still takes the service, his gasping for breath making his faith even more memorable, a Wordsworthian spot of time worthy of recall in darker moments in the struggle to “retain that sudden downrush / Of the numinous that was supposed to change us”. Poem seven expresses the sense of hard-won joy through another lyrical presentation of a second wedding. On this occasion, no clouds foreshadow failure but as the bride stands at the door, a wind blows her veil up like a candle flame or flower:

The guests are gathered in the church at Salle

The light falls on the floor;

For all eternity the rose

Stands at heaven’s door.

But the sequence and whole book ends in the altogether wilder landscape of St David’s, Wales. The final poem suggests such rose and flame moments are but parts of the coherence of a life where experience must inevitably consist of “Innocence and loss, hope, wisdom, regret and thanksgiving”. Exile and the Kingdom intends to convey this in full. Although propelled most often by loss of a loved one, the burden of the book remains love not grief. It matters little whether we share Davies’ particular form of faith, since what comes strongly from these pages is her concern for the way we treat each other, our overloaded preoccupation with ourselves, how our acts and choices are affected. Poems like these themselves form spots of time for the reader and I’m not going to forget their human concern for what love is and does.

Lovely overview of a much-neglected poet. There’s a sort of egregious repetition of the reviewer’s own self-limitation which should prompt further reflection. Davie’s ‘tradition’ wells up from the “sudden downrush of the numinous” and this is hardly unique — and Davie’s has always been existentially scrupulous, and faithful to her own contingencies as I recall from earlier volumes. I will certainly order a copy of this new one. Public opinion of the degraded and degrading sort, generations of lazy spiritualism, makes such poetry rare. Less there be any misgiving, I go to this blog for respite and envigoration and, as here, find what I need. Thank you, Martyn.

LikeLike

Many thanks Tom. Really appreciate your interest in the blogs, this one in particular. To be honest, confessions of my own self-limitations are both wholly reflex and carefully uncensored on my part. I watch myself doing it as a teacher on a daily basis as a matter of pedagogic choice, hear myself do it in poems and in literary criticism too. It’s no doubt deeply rooted personally (which I’d rather leave unfathomed); at the same time I’ve come to understand it also as preemptive strikes against the kind of fundamentalism that I find both false and terrifying. And apparently so attractive to so many people around the world these days. I’m a thorough-going materialist really, though have lived with a whopping big streak of spiritual yearning for as long as I can remember. Out of the argument with ourselves as Yeats said . . . [I tend to do that as well – ellipses. The last word is never the last word]. There – finished now.

LikeLike

Materialism has undergone a transformation in our time. The downrush of noumenal would not necessarily involve objective knowledge of anything beyond matter. You are probably a phenomenologist. The happily retired Archbishop of Canterbury would and has argued for materialism in his new writings on language. Brave new world. Anyway whatever the tensions in your makeup we are the beneficiaries thereof.

LikeLike

I think I may well be a phenomenologist (apologies to Plath). Doing a BBC radio programme about the Rilke translation I did ages ago I sat with Rowan Williams on the sofa at Lambeth Palace and had what felt like the most amazing chat about that and many things. It was recorded but the recording has since been lost which is a tragedy. In the whirl of the moment I hardly remember any of it. One point was that the world was saturated with meaning, or it can feel so. I think that is something to do with the noumenal. It’s opposite is the materialist, valueless desert.

LikeLike

See now Williams, The Edge of Words. Great book. ‘Materialist’ too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] understanding of what constitutes a good poem”. Evidently, she sides with the magazines (see my recent review of Davies most recent collection). In contrast, Martin Malone confesses he’s not so sure where he […]

LikeLike

[…] January this year, I posted a review of Hilary Davies’ powerful new collection, Exile and the Kingdom. In what follows, she has been kind enough to answer a few questions which presented themselves as […]

LikeLike

[…] like Hilary Davies’ Exile and the Kingdom more successfully tackles many of these issues. (I reviewed Davies’ book in January 2017 and have also posted an interview with […]

LikeLike