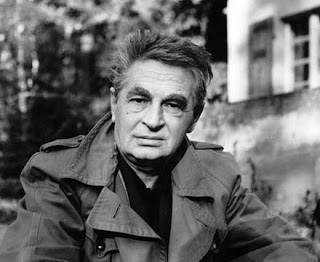

I have been working off and on over the last year on translating the third collection by the German poet, Peter Huchel. I hope to complete this for publication in the next few months and here (over this and my next blog post) I have been gathering information about his life and times. I’ve found people know of his work but not in much detail. In a working life that saw him through some of the most traumatic events of European history, Huchel published only 4 collections of poetry in 1948, 1963, 1972 and 1979. Throughout his career the substance of much of his work is his vivid observation of the natural world, moving gradually towards a usually brief, free verse form, a withdrawal from the personal and a steadily darkening vision which comes to be dominated by elegy and lament.

Peter Huchel was born Hellmut Huchel in 1903 in Lichterfelde (now part of Berlin). As a result of his mother’s ill health he was taken from the city to grow up on his grandfather’s farm at Alt-Langewisch, in the Brandenburg countryside near Potsdam. Huchel himself later argued “it is precisely the experiences of childhood, roughly between the ages of five and ten, that exercise a decisive influence in later years” (acceptance speech for the 1974 Literature Prize of the Free Masons). If this period was something of an idyll then it was shattered dramatically and forever by the death of the eleven year old boy’s grandfather and the outbreak of war in Europe.

After defeat and his country’s humiliation at Versailles, Huchel, now 17 years old, took part in the conservative Kapp-Putsch against the Weimar Republic in 1920 which was fuelled by a resentment against the German government for signing up to the punishing conditions of the Treaty of Versailles. In the fighting associated with the failed coup, Huchel was wounded and it was during his recovery in hospital that his sympathies for socialism and Marxism fully developed.

From 1923 to 1926, Huchel studied literature and philosophy at the universities of Berlin, Freiberg and Vienna. Though always temperamentally an outsider, these were years of political, economic and artistic ferment (though ultimately something Huchel would react against) and in the final years of the 1920s he travelled to France, Italy, Greece, Hungary, Romania, Turkey. In 1930, he changed his first name to Peter. His early poems were being written and published from 1924 onwards and were already strongly marked by the atmosphere and landscape of Brandenburg. He appeared out of step with the times, writing nature lyrics, using conventional metre and rhyme, though the natural landscapes he portrayed were far from pastoral. The rural world he grew up in was providing ways of articulating concerns about the shortcomings of the world about him: his close observations of Nature showed her as a harsh mistress and the poverty and suffering of Huchel’s Brandenburg peasants were both very real and politically charged.

Working as an editorial assistant for Die Literarische Welt by 1932, Huchel’s poems won a prize and his first manuscript was accepted for publication under the title Der Knabenteich (‘The Boy’s Pond’). In 1934, Huchel married Dora Lassel but with the rise of Hitler in 1933, Die Literarische Welt ceased publication and Huchel withdrew his book partly for political reasons. He fled to Romania for a while and was deeply troubled that the Nazi’s liked his work, reading into it as they did a version of the blood and soil nationalism they hoped to foster. A few of his poems were published but by 1936 he was refusing permission and he did not publish a new poem during the rest of Hitler’s rule. Instead, he withdrew to the Brandenburg countryside but was eventually drafted in 1941, ending the war in a Russian prisoner of war camp.

With the fall of the Third Reich, Huchel enthusiastically shared the democratic and socialist optimism of many of his compatriots about the reconstruction of Eastern Germany offering a vision of freedom and equality to all. He began working for East German radio, published his first collection, Gedichte (‘Poems’), in 1948 and in 1949 became editor of the influential poetry magazine Sind und Form (Sense and Form’). Huchel’s poems were applauded both for their craft and evident socialist undercurrents though he did not satisfy some who demanded much more explicit support for the German Democratic experiment. Huchel’s dark rural landscapes offered at best equivocal support for the socialist regime and his instinctively conservative harking back to childhood and the natural world (rather than the modern revolutionary transformations of human society) were rightly seen by many as falling far short of the expected unquestioning celebration of the GDR’s project.

Here’s Huchel’s ‘The Polish Reaper’ – from this period – as translated by Michael Hamburger. Compared to Huchel’s later work, there is an exclamatory and ‘poetic’ quality to many of these lines (despite being nominally spoken by a migrant worker in Germany). Also the political content is more explicit in the fields mowed but not owned, the poor conditions of the workers and the rather hefty symbolism of the returning eastwards to a red dawn!

Do not cry, golden-eyed frog,

in the pond’s weedy water.

Like a great conch

the night sky roars.

Its roaring calls me home.

My scythe shouldered

I walk down the bright main road,

Dogs howling round me,

past the smithy’s grime

where darkly the anvil sleeps.

Down by the outwork

poplars are drifting

in the moon’s milky light.

Still the meadows exhale heat

in the crickets’ screeching.

O fire of the earth,

my heart holds a different glow.

Field after field I mowed,

not one blade was my own.

Blow, autumn gales!

On the bare boards of lofts

hungry sleepers awaken.

Not alone I walk

down the bright main road.

At the rim of night

the stars glitter

like grain on the threshing-floor,

where I go home to the eastern country,

into morning’s red light.

I’ll continue Peter Huchel’s life story in my next post.

Fantastic, i’m looking forward to reading more.

LikeLike

Thanks Robert hope you are doing well

LikeLike

Thank you for posting about Peter Huchel. First read his work in ‘Second World War Poems- chosen by Hugh Haughton’ ( 2004) and have been keen to find more.

LikeLike

Thanks Michael. I don’t know that selection. Is it the Hamburger translation again?

LikeLike

A good start is Ian Hilton’s introduction: Plough a lonely furrow. Next to Michael Hamburger’s he was translated by Henry Beissel (A thistle is his mouth) and Robert Firmage. And if you do understand German, you could read my biography: Der heimliche König. Leben und Werk von Peter Huchel. Or my edition of Huchel’s letters: Wie soll man da Gedichte schreiben.

Thank you Martyn for your blog and work on Huchel. If you have questions, doubt about the meaning of lines, don’t hesitate to contact me. Kind regards,

Hub Nijssen

Radboud University Nijmegen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks, Hub. I’ve just sent an email to you and would be delighted to have a discussion bout Huchel’s work.

LikeLike